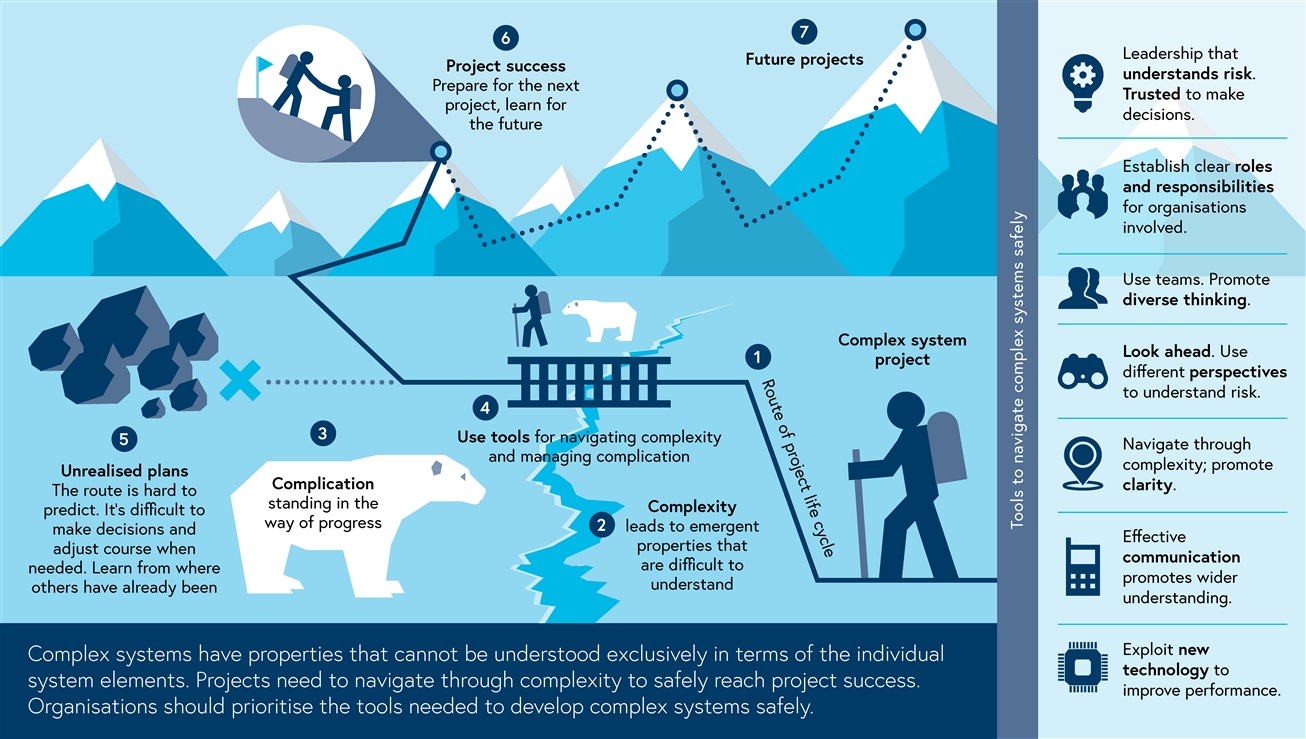

To develop a system that is safe, a sufficient understanding of its properties is needed. For a complex system, this must include emergent properties, without which understanding is not complete and confidence in its safety cannot be claimed. Our new flyer has been created to help managers and engineers understand complexity and emergent properties to guide systems more clearly and safely through their life cycles. In doing so, there is greater potential to develop safe products that are fit for purpose, produced efficiently, and supported effectively. Download the flyer for free: Safely managing the emergent properties of complex systems

The diagram below demonstrates how to navigate complex systems safely:

Our flyer also presents the objectives for engineering managers, which includes sustainable thinking, exploiting technology for deeper management insights, as well the objectives for engineers, which includes a better understanding of emergent properties and when to take action.

Download the flyer for free: Safely managing the emergent properties of complex systems

All feedback on this paper is welcome. Log in to your IET EngX account and leave your comments below.