I have some questions about protective equipotential bonding.

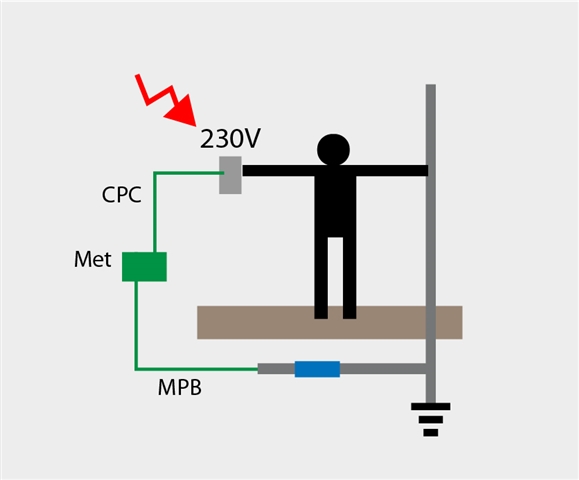

main protective bonding .

I understand the principle, that with no potential difference no current will flow

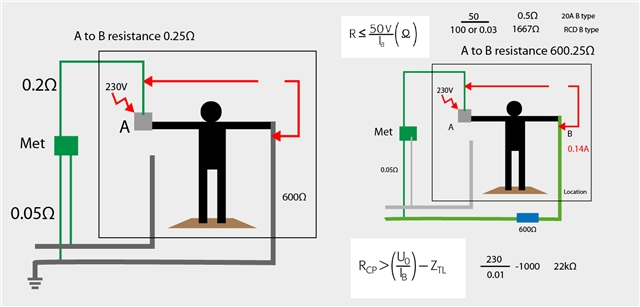

I'm wondering about volt drop.

You will get volt drop if you have a flow of current.

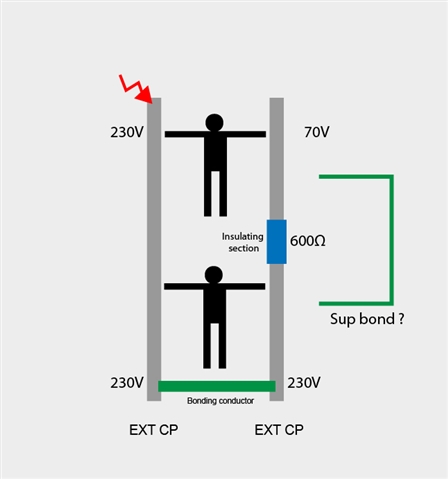

So if you have two extraneous CPs and you are in between them.

One has 230V on it, and the bonding raises the potential of the other, Ext CP to 230V so no difference

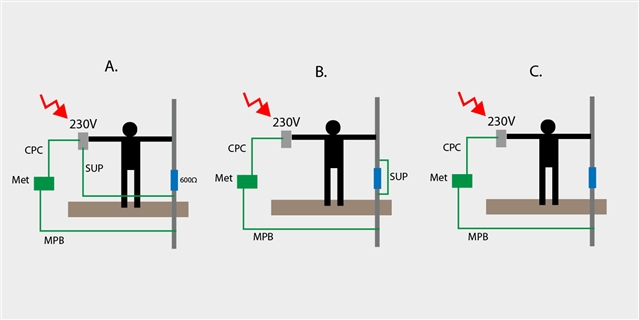

Now if an insulating section was put in between one of the Ext parts as in the example 600Ω

I am wondering what would be the outcome.

This is a standing voltage, and current would not flow between the equal potentials ?

(If there was no other path.)

But would it flow between the 230v and 70v example.

Would you actually get this volt drop?

Picture might say it better.