On this day in (engineering) history…

August 13, 1889 - William Gray of Hartford, Connecticut patents the payphone

You're having a bad day. Your spouse is seriously ill, and you need to get help. You need a phone, but don't have one. Ask a neighbour…they won't let you use theirs. You go out searching for a phone, any phone to use. But nobody has one, and those that do refuse your pleas to call a doctor. What do you do?

If you're William Gray, you invent and patent the payphone.

Everyone's nightmare

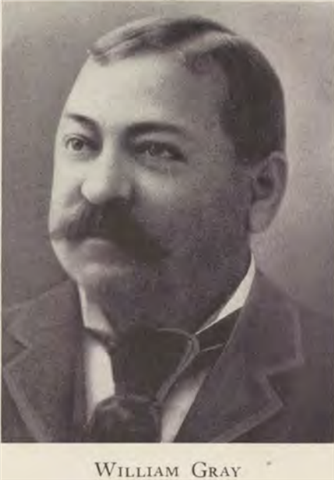

William Gray's father, Neil, thought his son needed a respectable job, so he sent him to work at a drug store. The druggist told Mr Gray the young man spent his time in the basement tinkering with anything he could get his hands on and should try something else. Next, this son of Scottish immigrants to the US began work as a polisher at an armoury before joining Pratt & Whitney (the future aero-engine maker). After fifteen years with the company, Gray became their Chief Polisher.

William Gray. Baseball fan, inventor of the baseball chest protector

and the payphone. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The story goes that William's wife was ill and needed a doctor. But this was 1887 (or 1888, the stories differ), and while there were telephones in peoples' homes and businesses, they were relatively rare. Not having a phone in his home, Gray walked the four blocks to a nearby typewriter factory to ask to use theirs. He was refused. He eventually found what he was looking for and called a doctor. Luckily, his wife made a full recovery, but this emergency was the root of what he did next.

How do I pay?

William had been turned away from other peoples' phones because he was not a subscriber. Call time was paid for on a monthly subscription to the local telephone exchange. 'Dead heads,' people who used the phone of a business or householder without paying, became a big problem.

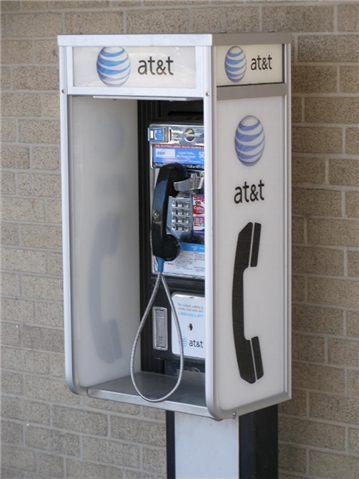

AT&T payphone in San Antonio, Texas, 2006. Source: Wikimedia Commons

One solution was the phone booth, where a customer could call for fifteen cents. An attendant would take the money and place the call for the customer. Another solution was the Pay Station, where a business would operate a number of telephones, and customers would pay the attendants. These appeared as soon as 1878, but were only worthwhile if the attendant was in attendance.

The voice is heard then becomes clear

The telephone didn't appear out of the blue, and there is much dispute surrounding its origins and development. Claim and counterclaim in the courts and the media have not made matters less complicated.

Engineers and inventors worked on the science and technology behind the device for decades before Alexander Graham Bell's 1876 patent. Belgian engineer Charles Bourseul was the first to suggest that sound could be transmitted with electricity (1854), but he was never able to produce a receiver to carry the human voice successfully.

Later, in the 1850s, Italian-American inventor Antonio Meucci installed electrically powered devices he called 'telettrofoni' to communicate between the rooms of his home. In the 1860s, German inventor Johann Philipp Reis developed devices using membranes with metal strips to transmit sound electrically.

Bicycle payphone in Uganda. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Ahoy!

In the 1870s, Alexander Graham Bell and the less well-known inventor Elisha Gray were developing equipment that would form the basis of the telephone we know today. Gray's idea revolved around using a harmonic telegraph to carry the human voice. While Bell considered this, he abandoned the idea in favour of using a diaphragm of goldbeater's skin with a frame of magnetised iron very close to the centre. This would vibrate in front of an electromagnet in a circuit. Another diaphragm would act as a transmitter.

Bell's idea won out, not least because he was the first to patent it. But even this is in dispute because Gray filed a caveat (a short-term place holder for an impending patent application) for his invention on the same day Bell lodged his application.

Legend has it that when asked what someone should say when answering a phone call, Bell suggested, 'Ahoy!' This hasn't caught on.

Making the right call

Like many first attempts, William's first payphone design was less than ideal. He placed a cover over the receiver, which was removed by placing a coin into a slot. With no way of being sure the user would not, could not, make multiple free calls once the cover was off, the idea was dropped. More false starts followed before he arrived at a solution.

Initially, Gray's payphones worked on trust. The user would make the call; when the call ended, the operator would tell the user what coins to put in. Gray devised a way to make the coin set off a bell to alert the telephone operator that money had been put in the machine. Coins of different denominations would slide through different chutes, setting off different bells, indicating the correct change had been used.

William's first patent was granted (United States Patent Number 408,709 for "Coin-controlled apparatus for telephones.") on August 13, 1888. The first payphone was installed on a street corner outside a bank in Hartford, Connecticut in 1889.

In 1891, William Gray left Pratt & Whitney and founded the Gray Telephone Pay Station Company, which began rolling out his payphones on posts and in 'cabinets,' or wooden phone booths, across the United States. By 1902, there were 81,000 early payphones across America.

Payphones with built-in web browser, Shanghai, China. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Return of the Coin

If money was deposited before knowing if it could be connected or before the operator could say which coins should be pushed into the slot, that money was forfeit. This remained the case until 1908, when Otto Forsberg, an electrical engineer at Elisha Gray's Western Electric (then AT&T's industrial arm), developed the coin return.

Western Electric joined forces with the Gray Telephone Pay Station Company and worked to produce the Western Electric model 50-A, the first coin-returning payphone, which appeared in 1911. Within a year, 25,000 of the new phones were in New York City alone. They were placed, often in large numbers, where people would congregate or in areas of high footfall, such as banks, bars, pharmacies, post offices, or railway stations.

A century after their invention, there would be two million payphones in the United States. They took off right around the world. The most iconic phone booth, or phone box in the UK, would be the red phone box designed by Giles Gilbert Scott, red because it was so easy to see.

The payphone would become part of popular culture, appearing in films – from action thrillers to romantic comedies, where their role would become nearly as important as the actors – and music, where they would be facilitators of love, loss, and betrayal at any time of day, but especially at night.

The end of the line

Once ubiquitous around the world, payphones are now an ever-decreasing rarity, overtaken by other and more mobile forms of communication. First invented in 1973 by Motorola, the mobile cell phone didn't take off until it could be made at a dimension smaller than the size and weight of a large household brick. When that happened, the mobile cell phone truly took off. Now, the number of phones in people's hands can be counted in the billions, while payphone boxes and sites have become empty, unused, and eventually removed.

Red K6 telephone box, St Paul's Cathedral, London,

United Kingdom, 2012. Source: Wikimedia Commons

William Gray's success rapidly made him one of Hartford, Connecticut's largest employers. But sadly, he never saw his invention, fitted with the coin return, become a 20th-century infrastructure giant.

He died from a stroke on January 24, 1903, at the age of fifty-two. He was survived by his wife, whose illness only fifteen years earlier inadvertently made so much possible, and four children.

What he did live to see was that he rapidly became one of Hartford, Connecticut's biggest employers, picking up twenty-three patents for his work along the way.

Questions, questions

Like many technologies, the telephone's origin story is complicated and muddy, with numerous inventors able to claim to be 'the father of the telephone.' Perhaps our idea of the single, solitary, and slightly eccentric inventor is not a realistic one. Or is it?

By Stephen Phillips - IET Content Producer, with passions for history, engineering, tech and the sciences.

By Stephen Phillips - IET Content Producer, with passions for history, engineering, tech and the sciences.