October 8, 1829 - Stephenson's The Rocket wins The Rainhill Trials

Your business is booming, demand for your product is growing by the day. You produce it with the latest technology, but technological wonders end when it leaves the factory gate. The product must travel by horseback, in horse-drawn wagons or canal boats pulled by horses.

What to do? You ask the best brains in the country to produce the best locomotives in the country and test them at the Rainhill Trials - where one machine is far ahead of anything else – the 'Rocket.'

The 'Rocket', photographed on display at The Science Museum (now displayed at Locomotion in Shildon, County Durham) Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Problem

By the 1820s, the Industrial Revolution drew people in ever greater numbers from the countryside to towns and cities. They found work at the new steam-powered factories popping up all over the country. Raw materials and products alike were pouring out of coal mines, iron works and cotton mills to keep pace with ravenous consumer and industrial demand. Transport was proving a real bottleneck.

In Lancashire's great 'cottonopolis' of Manchester, the need for change was obvious. Its cotton industry relied on the port of Liverpool, thirty-five miles away, to bring in raw cotton and export finished cloth.

A canal boat would take 12 hours to move between Manchester and Liverpool. Canals were slow and expensive to develop. Mill owners also suspected canal operators of profiteering off the cotton trade. Roads in the area (as with most roads in Britain at the time) were poor. Wagons and coaches were a little quicker, making Liverpool to Manchester in three hours. But there was a continual danger of crashing or overturning - risking life, limb, and whatever goods they carried.

The Potential Solution

The Liverpool corn merchant Joseph Sanders and Manchester mill owner John Kennedy are said to be the originators of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. Land agent, speculator, pioneering railway enthusiast and promotor William James inspired them with his vision of a nationwide rail network rapidly moving people and goods. In 1824, one Henry Booth became Secretary and Treasurer of the newly formed Liverpool and Manchester Railway Company.

A lithograph of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway crossing the Bridgewater Canal at Patricroft, by A. B. Clayton. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Rainhill Trials – Stoking the Fires

On May 1, 1829, an advert appeared in the Liverpool Mercury, announcing the Liverpool and Manchester's need for a locomotive better than any that had previously been built.

It invited entries for a competition to choose the best design, with Trials to test the most promising candidates. The company would offer £500 over and above the cost price for the winning design. This Trial would be run over a one-and-a-half-mile-long track that was purpose-built at Rainhill, Lancashire.

The rules stipulated that each locomotive should pull a load three times its own weight, which would be no more than 4.5 imperial tons. Each engine would run ten journeys from the Starting Post to the End Point and back to the start, the equivalent of Liverpool to Manchester, some thirty-five miles. When that was complete, the engine would be refuelled and rewatered before being fired up for another ten journeys, the equivalent of the thirty-five miles from Manchester to Liverpool. The locomotives would hit full speed for thirty miles of this journey, with a minimum speed of ten miles per hour.

There would be three highly regarded judges; John Kennedy had worked on improving spinning machines in the textile industry. He was also an avid supporter of railways but appears to have taken little part in the Trials.

John Rastrick was a partner in Foster, Rastrick & Co, whose Stourbridge works had already built locomotives for the United States. Rastrick had conducted research for the Board of Directors of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway; his notebook on the Trials has been a mine of information about the event.

Nicholas Wood was the Chief Engineer at Killingworth Colliery, where he had worked with steam engines for 15 years. He was also a close associate of George Stephenson, who also began working with steam engines at Killingworth.

The response to the initial newspaper ad overwhelmed the company, and the Board eventually chose ten finalists. Of these, only five made it to Rainhill.

They included George and Robert Stephenson's 'Rocket,'; 'Perseverance,' designed and built by Timothy Burstall; 'Sans Pareil,' designed and built by Timothy Hackworth; 'Novelty,' designed and built by John Braithwaite and John Ericsson – also the very first 'tank' engine; and finally, Thomas Shaw Brandreth's 'Cycloped.'

Showtime

When the Rainhill Trials eventually fired up, ten to fifteen thousand people turned out to witness the spectacle. Bands provided music, to add to the party atmosphere and the local pubs did a roaring trade, one renaming itself 'The Railroad Tavern.'

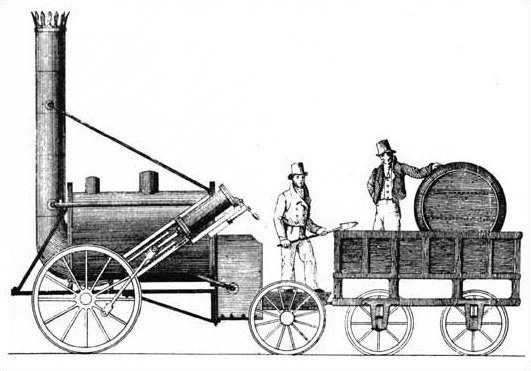

The 'Rocket,' designed by George and Robert Stephenson Source: Wikimedia Commons

There is little agreement on exactly how fast 'Rocket' moved during the Trials, although all agree it was the first machine to attempt 'the Ordeal,' as it had been billed. Without carriages, it could reach a top speed of 30 miles per hour. At the Trial, it pulled a full load at a speed of (depending on sources) 12 miles per hour - pushing and pulling the 13 tons in its wagons (including two filled with stone) backwards and forwards over the course without a problem. This would prove unmatchable.

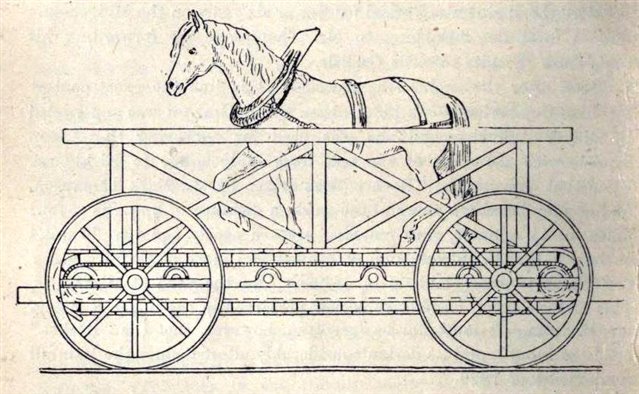

The strangest entrant was also the first to drop out. 'Cycloped' featured a flatbed wagon, with power provided by a horse walking or running on a treadmill serving as a drive belt. Sources differ on whether this was a serious entry, how many horses were needed to run it and what eventually happened. One source suggests the horse (one only) fell through the drive belt onto the tracks following an accident.

Thomas Shaw Brandreth's 'Cycloped' Source: Wikimedia Commons

Whatever happened, 'Cycloped' was withdrawn from the Trials, but the concept did briefly catch on in the USA, being tried out by the South Carolina Canal and Railroad Company.

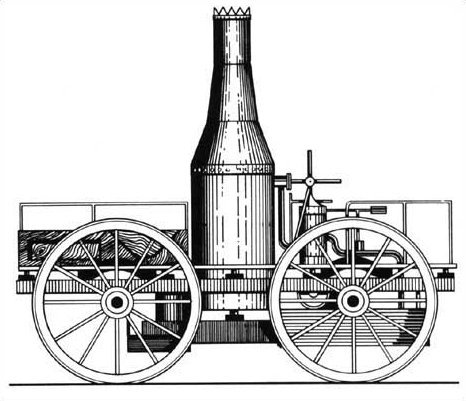

Timothy Burstall's 'Perseverance' Source: Wikimedia Commons

Timothy Burstall designed and built the next contestant, 'Perseverance,' at his factory in Edinburgh. The locomotive arrived at Rainhill in a state of disrepair after being damaged in transit. Burstall persevered for five of the six days of Trials to get his machine back in competition. He was successful, with the locomotive running on the last day. It could only reach a speed of six miles per hour, less than the ten miles per hour laid out in the rules, so Burstall was forced to withdraw his 'Perseverance.' He and his colleague, John Reed Hill, were given £25 in compensation.

The serious competition was between George and Robert Stephenson's 'Rocket,' John Ericsson and John Braithwaite's 'Novelty' and Timothy Hackworth's 'Sans Pareil' (from French, 'without equal').

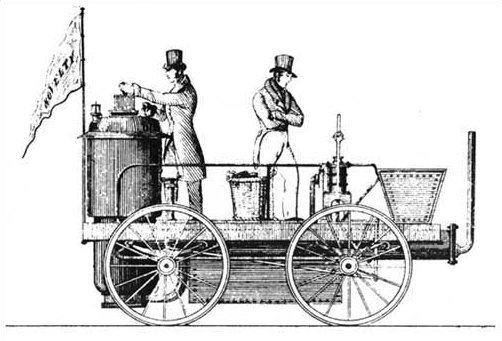

'Novelty' certainly had speed, reaching thirty miles per hour with passengers during a demonstration run before the Trials. During the Trials, the engine reached twenty-eight miles per hour (or twenty-four, depending on the source) before the boiler was starved of water, which forced a stop for repairs. On October 10, 'Novelty' suffered a burst boiler pipe, which drowned the fire. The crowds' favourite was now out of contention.

Ericsson and Braithwaite's 'Novelty' Source: Wikimedia Commons

'Sans Pareil' was already a little overweight for the Trials. Its design was regarded as old-fashioned, in comparison to the 'Rocket,' with its vertical cylinders giving the machine an awkward, waddling gait.

Its engine burned so inefficiently that much of the fuel coke was ejected through the chimney, unburnt, a flaw rooted in the powerful draught drawn through the fire by the engine's blastpipe. Still, fuel cost money and this could not be overlooked.

'Timothy Hackworth's Sans Pareil' Source: Wikimedia Commons

While 'Sans Pareil' did reach a speed of fifteen miles per hour, it suffered a breakdown and found itself out of the Trials.

Why the 'Rocket' was a (relative) rocket

The replica 'Rocket' beside the Albert Hall, 1979 Source: Wikimedia Commons

'Rocket' came out on top at the Rainhill Trials because of its superior power-to-weight ratio. It was a four-wheeled locomotive built with speed and reliability in mind and less focus on pulling power. For non-specialists, a steam engine runs by burning coal in a firebox. Heat from the fire moves into a water tank (the boiler) through a metal tube (the 'firetube'). This warms the water to the point where it produces steam. The hotter the water, the more steam.

Until 'Rocket,' steam engines used a single firetube to heat the boiler. Back in 1825, George and Robert Stephenson built the steam locomotive 'Locomotion 1.' Its boiler used a single firetube measuring 2.8 metres in length and 500mm in diameter, giving a surface heating transfer area of 4.4 metres2.

Henry Booth, Secretary of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, had a brainwave, suggesting multiple, narrower fire tubes to heat the boiler. In the 'Rocket's' boiler, there were 25 1.8-metre-long tubes, each of 75mm in diameter. That produced a surface heating transfer area of 10.6 metres2. Such an arrangement supplied more steam and more power from the engine whilst keeping the machine within the Trials' weight limit.

Another innovation featured in the 'Rocket' involved re-using exhaust steam from the power cylinders. Previously, this exhaust had been lost into the atmosphere. Timothy Hackworth (designer of the 'Sans Pareil') had developed a blast-pipe to redirect this wasted air into a low-pressure area below the chimney, in front of the firetubes. The low pressure drew heated air into the firetubes and through the firebox at an even greater rate, producing more heat from the fire and more heat for the boiler. The machine was now self-regulating.

Share your thoughts

How can we use our railways to their fullest potential?

By Stephen Phillips - IET Content Producer, with passions for history, engineering, tech and the sciences.

By Stephen Phillips - IET Content Producer, with passions for history, engineering, tech and the sciences.