On this day in (engineering) history…

December 17th, 1903 - The Wright brothers make the first controlled, powered, heavier-than-air flight

In Greek myth, father and son team Daedalus and Icarus made wings to escape their prison on the island of Crete (accounts vary). Made from bird feathers, blanket threads, leather and…wax. ‘Follow my flight path and don’t fly too close to the ocean or the sun!’

Icarus followed his father’s instructions until, becoming overconfident, he flew upwards, ever closer to the sun. The wax holding the feathers to the wing frame melted, and Icarus felt the pull of gravity.

Thousands of years later, at Kill Devil Hills, for brothers Wilbur and Orville Wright, there was no chance of following Icarus. Their heavier-than-air craft, ‘Flyer,’ made four flights. In the first, ‘Flyer’ travelled 120 feet at a top speed of 6.8 miles per hour in 12 seconds. Over the day, its highest altitude was 10 feet. The world would never be the same.

----------

Childhood fascination

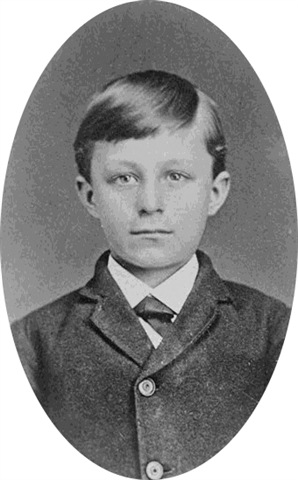

Wilbur As children. Source: Wikimedia Commons

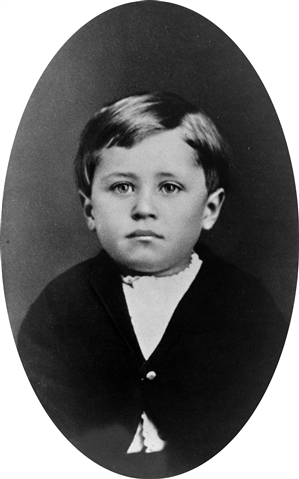

As children. Source: Wikimedia Commons  Orville

Orville

Wilbur (b. April 16, 1867) and Orville Wright (b. August 19, 1871) and their parents originally lived in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Their fascination with flight began one day in 1878 when their father returned home with a toy helicopter for the boys. It was based on a design by French pioneer Alphonse Pénaud, it was 30 cm in length, made from paper, bamboo, and an elastic band to spin its ‘blades.’ After playing it to destruction, they made their own replacement.

Pressing issue

In 1889, at the ripe old age of 15, Orville dropped out of school after his junior year to try his hand at a printing business. He designed and built his own printing press with help from Wilbur. After Wilbur joined the print shop, they launched The West Side News, a weekly paper published by Orville, edited by Wilbur. This became The Evening Item and went daily in April 1890, but the brothers had overreached, The Item lasted only four months.

On ya bike!

Regular printing jobs kept them going until December 1892, when the bicycle craze swept the world. The brothers responded by opening the Wright Cycle Exchange, a sales and repair shop in Dayton. They took it further in 1896 when they built and launched their own brand bicycle. Other events that year would influence the Wrights. Aviation pioneer and leading glider flyer, Otto Lilienthal was killed in a gliding accident in Berlin. He had spent years designing and testing his own gliders and was (is) regarded as a serious pioneer. His death pushed the Wrights to take their interest in flight considerably more seriously.

The Wright St Claire Bicycle. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Also, that year, Chicago aviation pioneer, Octave Chanute tested gliders over the shore of Lake Michigan, under a welter of publicity. Elsewhere, Samuel Langley, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, successfully flew a steam-powered, fixed-wing model aircraft. Chanute and Langley both had strong financial backing, as did other aviation pioneers. Not the Wrights. Their experiments, and their living expenses, would be funded by the Wright Cycle Co. (as the Wright Cycle Exchange had now become). The cycle business was surprisingly influential in the Wright Brothers’ journey to Kitty Hawk. It was more than ‘simply’ financial – much of the engineering was borrowed from bicycles.

Doing your own research

They began by reading everything they could find on the topic of flight. One source was the Smithsonian Institution, with Wilbur writing to ask the Smithsonian to send him everything they had on the topic.

The Brothers’ picked up on the work of Sir George Cayley, credited with being the ‘father of aviation.’ Sir George’s childhood fascination with flight led him to realise that what we now call fixed-wing aircraft would require separate systems for propulsion, lift and control. He set out the four ‘forces’ that allow an aircraft to fly: weight, lift, drag and thrust. Sir George developed the aerofoil shape of wings and the configuration that fixed-wing aircraft have adhered to ever since. Between 1799 and 1857, Sir George built a body of work that everyone who came after him has depended on.

But the Wrights put it all together and flew with it.

Flights of reality-based fancy

After all the reading, the Brothers realised that the main obstacle to safe flight was finding an adequate method of controlling a flying machine in the air.

For help, they turned to the true aviation experts: birds. They noticed that when a bird makes a manoeuvre, it alters the shape of its wings, especially at the tips. That allows the bird to ‘bank’ or ‘lean’ into the turn. Having experience with bicycles meant that Wilbur and Orville understood this already – a

cyclist does not simply turn the handlebars like a steering wheel; they lean into the turn.

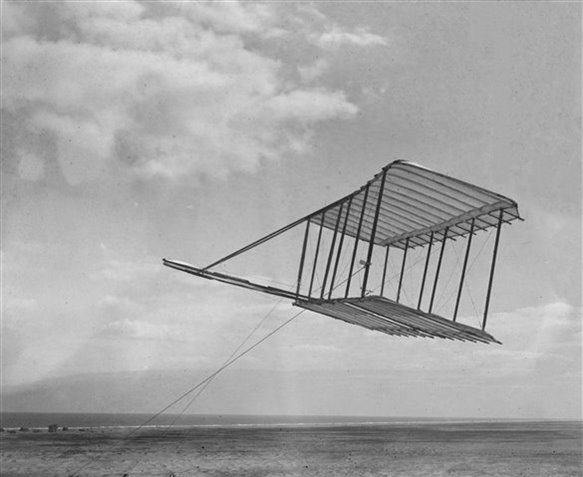

Wright Bros. glider, 1900. They were never photgraphed piloting this glider. Source: Wikimedia Commons

‘Banking’ or ‘leaning’ would also save the flying machine if it was tipped to one side by the wind in flight. They tested their findings (and Lilienthal’s) with their own homemade wind tunnel, which they used to test some 200 wing shapes. Received opinion at the time was that airplanes should naturally have stability. The Wrights’ hero, Otto Lilienthal, had tried to control his flights by simply shifting his body weight. Wilbur and Orville spotted the error. Giving the pilot absolute control was key to successful flight. Issues with wings and engines (they believed) had already been largely solved. Taking to the air with inadequately tested controls would, they realised, be fatal, as would lack of practice – something they and Lilienthal agreed on. But how to control the shape of aircraft wings in flight? The answer was wing-warping, something (so the story goes) that Wilbur spotted when he twisted an inner tube box at their bicycle shop. As a result, their first powered aircraft would have ‘drooping’ anhedral wings, which are inherently unstable but resistant to crosswinds.

‘Banking’ or ‘leaning’ would also save the flying machine if it was tipped to one side by the wind in flight. They tested their findings (and Lilienthal’s) with their own homemade wind tunnel, which they used to test some 200 wing shapes. Received opinion at the time was that airplanes should naturally have stability. The Wrights’ hero, Otto Lilienthal, had tried to control his flights by simply shifting his body weight. Wilbur and Orville spotted the error. Giving the pilot absolute control was key to successful flight. Issues with wings and engines (they believed) had already been largely solved. Taking to the air with inadequately tested controls would, they realised, be fatal, as would lack of practice – something they and Lilienthal agreed on. But how to control the shape of aircraft wings in flight? The answer was wing-warping, something (so the story goes) that Wilbur spotted when he twisted an inner tube box at their bicycle shop. As a result, their first powered aircraft would have ‘drooping’ anhedral wings, which are inherently unstable but resistant to crosswinds.

After testing kites during 1899, they moved onto gliders between 1900 and 1902, featuring configurations such as box-kites and biplanes. ‘Flyer,’ the first powered plane, was modelled on the 1902 glider (named after their final glider season). In 1903, it became the main training glider.

Building ‘Flyer’

The 1903 ‘Flyer' was built from wood and cloth textile. Spruce for straight members, such as wing spars, and ash for curved parts, such as wing ribs. The wings were set with a 1-in-20 camber covered by a type of 100% cotton muslin usually reserved for women’s underwear.

When they couldn’t find a suitable car engine, the Brothers commissioned an employee, Charlie Taylor, to build an engine from scratch.

Wilbur and Orville figured they would require four cylinders with a four-inch bore and stroke. The resulting powerplant weighed 82kg, developing 12 horsepower (9 kilowatts) at 1025 revolutions per minute. The body was made from cast aluminium, with the cylinders being bored on a lathe. Pistons and piston rings were made from cast iron.

All in all, Charlie took six weeks to build it.

The brothers also figured they would have more thrust from two relatively slow pusher propellers than a single fast one. Tested in the Brothers’ own wind tunnel, the 2.6-metre-long propellers were made from laminated spruce, painted with aluminium paint, and the tips covered with duck canvas. They were driven by a sprocket chain drive (bicycle influence popping up once again), one of which was crossed over - meaning the propellers turned in opposite directions - to minimise the risk of torque affecting the plane in flight.

The ‘Flyer’

‘Flyer’ weighed in at 274 kg, n without the pilot. The weight was distributed by placing the pilot left of centre, while the engine was placed right of centre. The engine being heavier than the pilot, by 14 to 18 kg, meant the right wings were ten centimetres longer than the left. The plane was configured as a canard biplane, ‘canard’ being the front-facing ‘tailplane’ placed ahead of the lifting surfaces.

Getting ‘Flyer’ into the air was one thing, controlling it was another. A carry-over from the gliders saw the pilot resting prone on the lower wing, with his head facing downward to reduce drag. He was placed in a hip cradle attached to wires linked to the wings and rudder. To steer, the pilot had to turn his body in the desired direction to move the rudder and warp the wings. The lever to control the elevators was held in the left hand, while a strut was held in the right hand. There were three instruments – a stopwatch recorded the flight time; an anemometer measured the flight distance in metres and a Veeder engine revolution recorder measured the propeller turns.

For take-off, ‘Flyer’ was placed on a dolly that ran along an 18-metre wooden rail track facing into the Kitty Hawk headwinds. It would land on ball bearing wheels made from bicycle hubs.

The winds were the reason the Kill Devil Hills near Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, was chosen for the tests. It was ideal for testing kites and gliders…and an underpowered experimental airplane. Without these winds, ‘Flyer’ might not have taken off at all.

Flying ‘Flyer’

The first attempted flight ended when ‘Flyer’ stalled three seconds into the flight, sustaining minor damage in the crash landing, which took three days to repair. The Brothers were ready to go again on December 17.

The Wright’s first flight last 12 seconds. Orville was the pilot. Note the drooping wings. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Wright’s first flight last 12 seconds. Orville was the pilot. Note the drooping wings. Source: Wikimedia Commons

That morning, the launch rail was placed on flat ground facing into a 20-mph wind. It was Orville’s turn to take the controls. The first manned, powered, controlled flight of a heavier-than-air machine took 12 seconds to cover 37 metres.

Between them, Wilbur and Orville made four low altitude, short, straight flights that day, taking turns at the controls. The final flight covered 260 metres in 59 seconds. Sadly, that would be the ‘Flyer’s’ final flight. A rough landing broke a front elevator support. A gust of wind blew the plane onto its side, turning it end over end, wrecking it in the process.

Wilbur and Orville returned, with the wreckage, to Dayton. While Orville repaired ‘Flyer,’ it would not fly again. The Brothers had proven their point and wanted to build an improved machine. That would be the Wright Flyer III and would not take to the air before 1905.

While Wilbur initially led the project, they became a team when Orville joined the effort. Orville was the better engineer; Wilbur was better with the business end of things and making the contacts that would sustain them over the years before and after that flight.

The Wright ‘Flyer’ at the National Air & Space Museum, Washington DC, after restoration. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Wright ‘Flyer’ at the National Air & Space Museum, Washington DC, after restoration. Source: Wikimedia Commons

To protect their discoveries and breakthroughs, the Wrights had worked in secret. So much so, that even today, it is not clear if the ‘Flyer’ that was wrecked after the fourth and final flight, or if Orville left out a few details as he rebuilt it. Over time, the strain of running a business and (what we would now call) a groundbreaking start-up proved too much. Wilbur died in 1912, aged 45, from suspected typhoid fever.

Orville took over the business, now the world’s first aircraft company, selling it in 1917 when he realised he didn’t have the necessary skills to make it successful. For the rest of his life, Orville took on roles promoting aircraft and flight, dying as the grand old man of aviation and deeply regretting the aeroplane’s destructive role in World War Two.

Legacy

Wilbur (left) and Orville (right) Wright. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Despite all the previous work they drew on to make that first flight, it was the Brothers that put everything together in one plane and combined it with a groundbreaking idea - three-axis control that allowed the aircraft to gain and maintain an equilibrium in flight. It made powered flight and the world we live in today possible.

Despite all the previous work they drew on to make that first flight, it was the Brothers that put everything together in one plane and combined it with a groundbreaking idea - three-axis control that allowed the aircraft to gain and maintain an equilibrium in flight. It made powered flight and the world we live in today possible.

‘Flyer’ is now on display at the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum in Washington DC, while replicas can be seen in museums across the United States.

Wilbur finally received his High School certificate in 1994 on his 127th birthday.

Share your thoughts?

How did you feel when you took your first flight?

What's the best flight you've ever experienced?

What do you love about aircraft?

By Stephen Phillips - IET Content Producer, with passions for history, engineering, tech and the sciences.

By Stephen Phillips - IET Content Producer, with passions for history, engineering, tech and the sciences.