On this day in (engineering) history…

September 10, 1846 - Elias Howe is granted a patent for the sewing machine.

Boston, Massachusetts, 1839. At the famous and highly regarded machine shop belonging to Ari Davis, a young man approaches Davis for advice or encouragement on a project of his, a knitting machine. Davis pointed out that the inventor was wasting his time, that he should be working on a sewing machine instead because there was money in it.

The inventor was not convinced, but a witness to that discussion had an idea that was crystalised when he stopped working because of a painful disability. Elizabeth, his wife, took on sewing work to bring in a little money. Watching her work, Elias Howe decided he could make Elizabeth’s job easier by inventing and patenting the sewing machine.

Elias and the Inventors

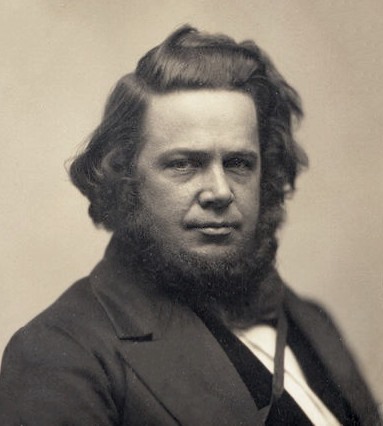

Elias Howe, Jr, inventor of the sewing machine, c.1850 Source: Wikimedia Commons

Born in Spencer, Massachusetts, in 1819, Elias Howe was not the only inventor in his family. His uncle, Tyler Wade, sailed to California to make his fortune - the hard cot he was forced to sleep in on board ship gave him the motivation and the idea to invent the spring mattress. Tyler was awarded the patent in 1855. Another uncle, William Wade, invented the Howe Truss Bridge, patenting it in 1840.

Elias had a lifelong interest in machines. In 1835, he apprenticed at a machine shop in Lowell, MA, which made a variety of machinery for the local textile industry. This shop had a reputation as a centre of research and development, doing more than simply making machinery for the industry, including building locomotives.

After the economic Panic of 1837, he briefly moved on to Cambridge, MA, before moving to Boston, where he found work at Ari Davis’s machine shop at 11 Cornhill.

By 1843, Elias was back in Cambridge, unable to work, but financially propped up by George Fisher, a childhood friend who had come into money. Fisher supported the family with an investment of $500, a room-workshop and living quarters (they moved into his house), all while Elias worked on his ideas for a sewing machine.

It was ever thus…

Like so many other inventions, Elias’s sewing machine was not the singular product of one mind having an ‘eureka’ moment.

Attempts to make a sewing machine go back to 1755 when German–American engineer Charles Fredrick Wiesenthal was awarded a British patent for a device using a needle with an eye on either end. The problem is this was not a true machine for sewing; instead, it was simply an aid for sewing.

It fell to English inventor and cabinet maker Thomas Saint to develop a sewing machine which carried several important features, which he hoped would sew leather and canvas. While he was awarded a patent in 1790, he never properly marketed his design, and there is no evidence he ever produced a working model, although, in 1874, Thomas Newton Wilson produced a working, if slightly modified, Saint machine.

In 1830, the American inventor of (among other things) the safety pin, Walter Hunt, designed a backstitch sewing machine, the first that made no attempt to mimic the work of the human hand. It has been claimed he initially refused to obtain a patent because of the impact it would have on the employment of seamstresses. When he did attempt to obtain a patent for his design in 1853, the Patent Office denied his application, because he had waited far too long. Elias Howe, with his 1846 patent, would retain precedence.

Magical machine

Drawing of the first patented lockstitch sewing machine, invented by Elias Howe in 1845 and patented in 1846, Source: Wikimedia Commons

How a sewing machine works looks mysterious because so much of it is hidden from the eye. To begin, placing the needle’s eye close to the point allows the needle – threaded from a cotton reel mounted on a spindle - to pierce the cloth from above without having to be pulled all the way through the fabric. Below the cloth, a shuttle would pass cotton from a second reel mounted in a bobbin through a loop in the first cotton line.

At a demonstration in 1845, Howe completed five seams before five seamstresses had completed one. A human could make 23 stitches per minute in fine linen, Howe’s machine could create 640. It would take 14 hours and 26 minutes for a person to make a gentleman’s shirt, where the sewing machine would take one hour and 14 minutes.

The effects were profound.

Suddenly, choice

Before the sewing machine, clothes were expensive, time-consuming to make and hard to come by. In the 18th century, a good dress was defined as a garment that could be passed from one generation to the next, with alterations to allow for changes in fashion. Individuals would own few garments (especially if they were poor) over the course of a lifetime.

The sewing machine changed all that. The time needed to produce garments of any kind fell dramatically, as did the cost. It was not only clothes. Sails, tents, awnings, bookbinding, flags and banners, trunks, saddles, mattresses, harnesses, umbrellas…all sorts of goods became easier to make, cheaper and more readily available to a far wider public than previously.

This invention changed everyday life in a way that few other machines have, and the effects are still with us - in online and bricks and mortar clothing stores, fashion pages of websites and magazines, sailing, camping, flying (think of parachutes) all would be far harder without the sewing machine.

Bad Luck

Elias Howe may have been an engineering genius, but he was no businessman. There were few buyers for his machine while it remained priced at $300, nearly $10,000 in modern money.

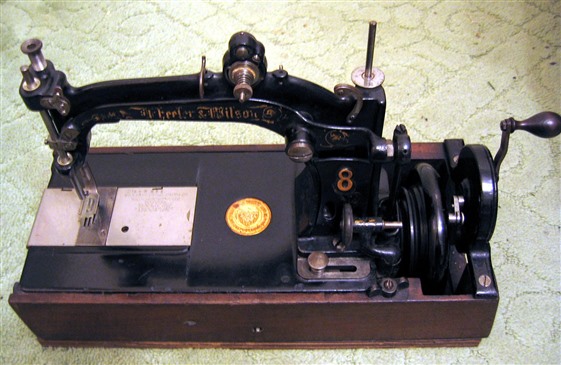

Competition - Singer Treadle Sewing Machine Source: Wikimedia Commons

Elias’s older brother, Amasa, left for London and sold a machine for £250 to one William Thomas, owner of a factory making umbrellas and corsets, amongst other things. Elias and his family soon joined Amasa in London, but a business dispute with William Thomas saw their money dry up. Elizabeth was forced by failing health to return early to Massachusetts. Poverty eventually did the same to Elias, but Elizabeth died in 1849, shortly after Elias returned.

By now, Elias could see that sewing machines were popular and making a lot of money for a number of manufacturers…just not for Elias. His patents were being infringed every day. Five years of lawsuits came to an end in 1854 in his favour. In 1856, Elias came to an agreement with a number of companies, namely I.M Singer, Wheeler & Wilson, alongside Grover and Baker – to create the first patent pool in US history, called The Sewing Machine Combination. The new grouping put an end to squabbles over patents (at least until Elias’s patent lapsed in 1877) and allowed everyone to concentrate on making money.

Competition - Hand-cranked Wheeler and Wilson Company machine, 1880 Source: Wikimedia Commons

Elias finally had some luck in the form of $2 million in royalties, making him very wealthy. Sadly, it could not buy him time after a life of poverty, misfortune, and ill health. Elias Howe died in 1867 at the age of 48.

His legacy is our obsession with fashion, clothing, and other textiles that we now take for granted. Meanwhile, The Beatles’ movie ‘Help!’ (1965) is dedicated to his memory.

Share your thoughts

Some technology does its job so well that it is difficult to reinvent. What inventions do you think fall into this category, and what do you think we will still be using in 170 years’ time? Leave your thoughts in the comments below

By Stephen Phillips - IET Content Producer, with passions for history, engineering, tech and the sciences.

By Stephen Phillips - IET Content Producer, with passions for history, engineering, tech and the sciences.