By Anne Locker

The electrical engineer and physicist Silvanus Phillips Thompson had an impressive and varied professional career. He became a professor at the University of Bristol in 1878 in his late twenties. He was the first Principal of Finsbury Technical College, where he also worked as Professor of Physics alongside William Ayrton. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1891 and was President of the Institution of Electrical Engineers in 1889, the same year it elected its first woman member. Thompson was well known for his publications, including Elementary Lessons in Electricity and Magnetism (1881), Dynamo-Electric Machinery (1888) and Calculus Made Easy (1910) – the last book is still in print.

What makes him a likeable as well as impressive figure is that he took the same meticulous approach to his hobbies as his professional work, while not taking his achievements too seriously. Thompson was a keen book collector, and his world-leading library of works on electricity and magnetism is one of the cornerstone collections of the IET Library and Archives. He was also an amateur botanist, geologist and etymologist. Not content with these hobbies, in the 1880s he took up painting in watercolour.

The development of Thompson’s interests and hobbies seem to follow the same pattern. Looking at his watercolours – there are six examples in the IET’s collections – we can see how he approached a new subject.

Exploration

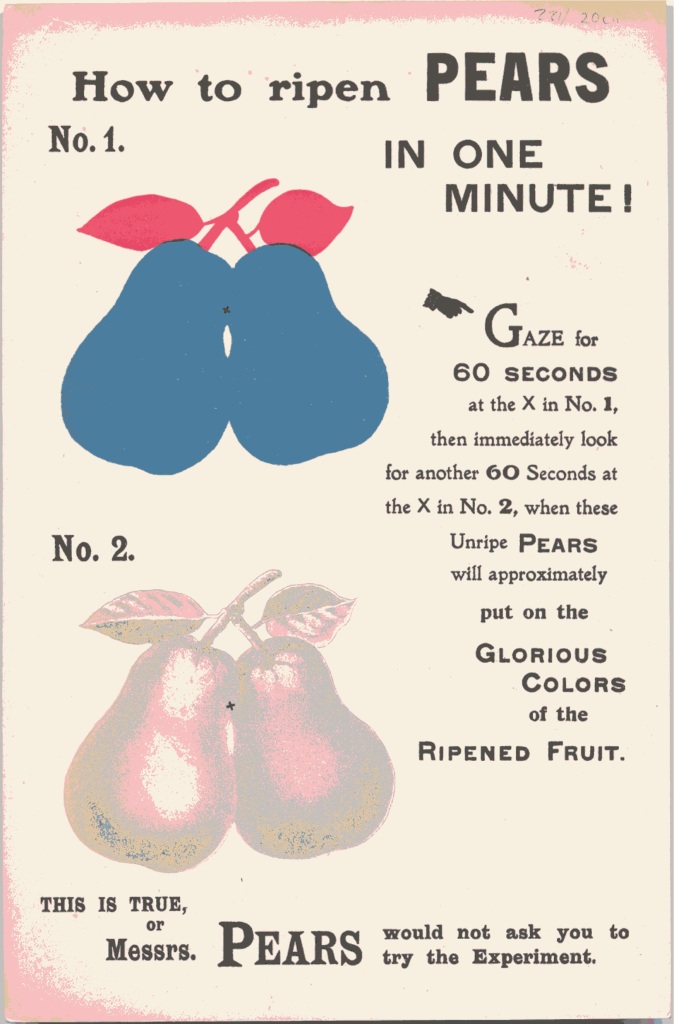

The first step was exploration and experimentation. Thompson would investigate any new area thoroughly, trying different tools and techniques and – where possible – collecting information (which fed his hobby of book collecting). He would gather resources on a subject and then classify and categorise them so he could easily find the information again. In his collection of pamphlets, there are several volumes on colour, optics and optical illusions, including this advert for Pear’s soap:

The earliest watercolour of Thompson’s in the IET collection was painted on the isle of Arran in 1889. This shows the mouth of the Sannox Burn, Glen Sannox.

Socialisation

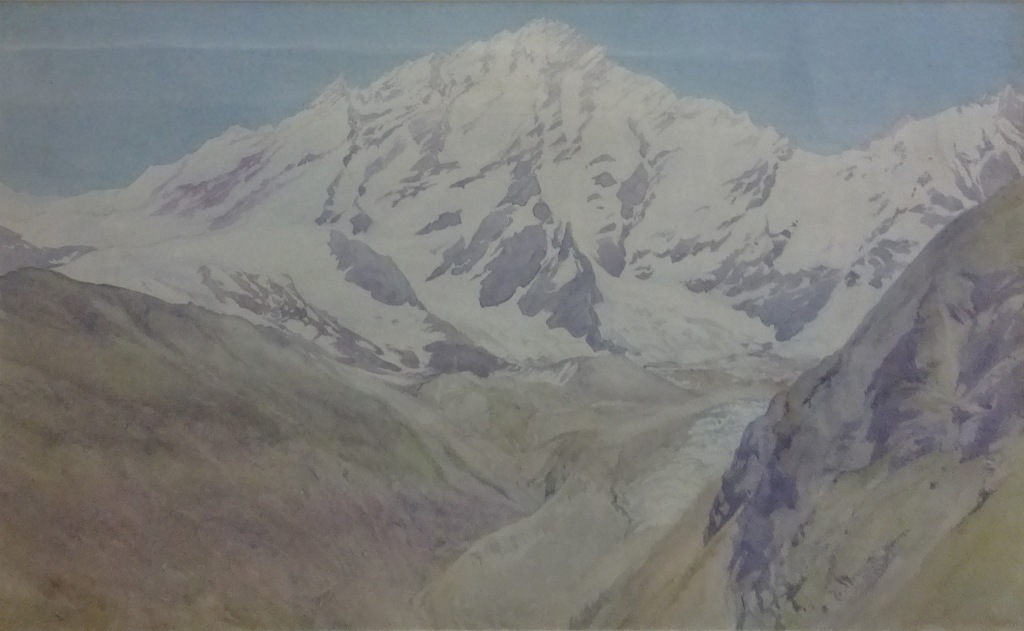

Having gathered information and experimented, Thompson’s next step was to find some company. He was a joiner: he was a member of many societies and organisations and often served as president. He met fellow artists on family holidays to Switzerland and in 1884 exhibited some of his watercolours and sketches at the Dudley Gallery in London. He joined the Royal Watercolour Society and also exhibited at the Alpine Club.

This painting from 1908 shows the Stein Glacier, near Berne.

Specialisation

In the third phase, Thompson focused on a specific subject or technique and honed his knowledge and expertise. In his rare book collecting, he focused on the work of William Gilbert and the history of the magnet. In his watercolour painting, he focused on ice.

After his death, his friend George Flemwell, wrote to his widow (and biographer) Jane Thompson:

As you know, Dr Thompson was never happier than when painting ice … And he revelled in it. So much so, in fact, that I remember being nervous for him planted for hours in midst of these treacherous seracs below the great ice fall on the Argentiere Glacier…

Jane Smeal Thompson and Helen G Thompson (eds), Silvanus Phillips Thompson: his life and letters (p. 307). London: T Fisher Unwin, 1920.

We can see the result of this adventure in Thompson’s painting titled Seracs, which shows the hazardous blocks of ice on the Argentiere glacier in the French alps. This was painted in 1913.

In the same year, Thompson travelled to Switzerland where he painted the Weisshorn from the Alpe de la Lee, Zinal. Coincidentally, the first person to climb the Weisshorn (in 1861) was a fellow physicist, John Tyndall.

A second painting of the Argentiere glacier was exhibited at the Alpine Club in 2015. It was priced at 15 guineas.

The supracrepidarian

So what is a supracrepidarian? It’s a word Thompson made up, and it does not appear to have caught on.

In 1907, Thompson had joined yet another society, the South Eastern Union of Scientific Societies, and was duly elected President. He used his presidential address to imagine a conversation with a ‘supracrepidarian’, or an amateur enthusiast. He concocted the word from Pliny’s proverb, ‘Ne sutor supra crepidam judicaret’ (‘Let the cobbler stick to his last’). Thompson thought that the last thing you should do was stick to your last, or restrict yourself to one profession. He defended the right of the amateur to indulge in science – and art – and find enjoyment in the work:

The happy day spent in the field or the forest among the birds and insects, or in the quarry with the hammer, writes its own record on the tissue of the brain. And, as with the phonograph, one may take out some cylinder long ago inscribed, and place it on the instrument, and … bring out the records of our happy field-days, and live them anew…”

Silvanus Phillips Thompson: his life and letters (ibid) p. 302

Thompson died in 1916. He was only 67 years old, but left behind an extraordinarily varied body of work. After his death, the Alpine Club exhibited over a hundred of his paintings and sketches – all completed on short holidays from his busy career. He remained a supracrepidarian to the end.