On this day in (engineering) history…

February 6, 1959, Jack Kilby of Texas Instruments files the first patent for an integrated circuit.

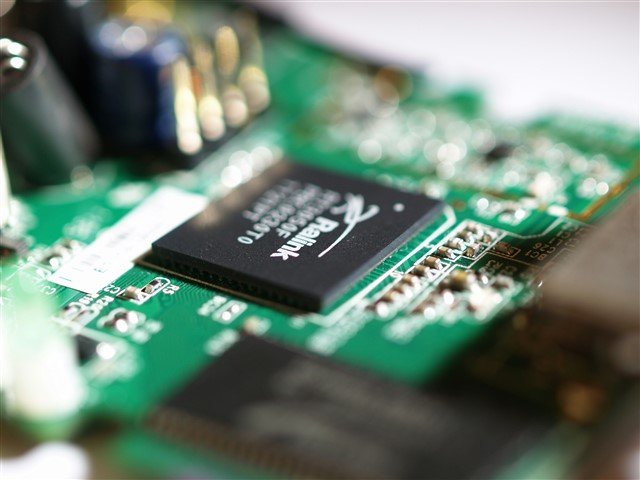

On the mild winters day of February 6, 1959, Jack Kilby, of Texas Instruments (TI) is granted a patent, one of more than 50 he would be awarded for his inventions. The invention protected by that patent would ultimately change the world and everything about human experience: the integrated circuit, popularly known as the microchip.

The story properly begins during the previous summer when Kilby joined Texas Instruments. He had become interested in miniaturising electrical components and Texas Instruments was the only company that would let him work on it full time. At this point, electronics was dominated by the reality that producing electrical devices required separate components such as transistors and capacitors to form a circuit, all of which required wiring to connect them. It meant building ever more advanced computers required too many individual components with their wiring to build a functioning device. This was called ‘the tyranny of numbers.’

In 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor just as Jack Kilby began classes at the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign. The (by now former) soldier returned after the war, picking up a Bachelor’s in Electrical Engineering in 1947. After moving to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, he accepted a job at Centralab. But he left when it became apparent the firm lacked the resources to allow him to work on miniaturising technology.

When Kilby started work at Texas Instruments (the only company that would allow him to work on miniaturisation full time) he found himself virtually alone in the building. His colleagues had left for their company mandated annual vacation, for which he was ineligible. Left to himself, Kilby began working on miniaturising electronic components.

The real breakthrough came when he realised the components could all be made of the same piece of material. The usual transistors, resistors, capacitors, their wiring and connectors could be ditched.

Kilby integrated a capacitor, a transistor and the equivalent of three resistors on the same chip. The prototype integrated circuit used a thin piece of germanium as a bulk resistor with a single bipolar transistor. There were four input / output terminals, a ground and gold wiring.

Many of the 50 or so patents Jack Kilby was awarded in his career, involved improvements to the microchip. One involved using the new integrated circuits to build the first computer to utilise integrated circuits, built by Texas Instruments for the US Air Force (1961) and guidance system for the Minuteman ballistic missile programme (1962).

In 1965, Kilby invented the thermal printer, which used integrated circuits.

His next move was to do something with the new invention. Jack began work in 1967 on the first calculator, the ‘Pocketronic,’ produced by Canon in 1971, which used three Texas Instruments integrated circuits. It sold for under $400, but at this stage a suitable display didn’t quite exist. Instead, results were printed onto thermal paper tape. The name was deceptive, because the ‘Pocketronic’ was the size of a paperback and didn’t fit into a pocket. Indeed, In this process he picked up a patent that still sits in the middle of modern pocket calculators.

Hewlett Packard used integrated circuits to produce the HP 9100A, a calculator / computer the size of a typewriter. While this was, for the time, a powerful piece of kit, it retailed for $4,900. Texas Instruments itself and Sharp Electronics joined the race to make a pocket sized calculator, using four or five microchips.

A new company called ‘Intel’ joined the micro scramble after buying back the rights to a chip it had sold to Japan’s Busicom. The Intel 4004 would become the very first commercially available microprocessor.

The HP -35 was a large, hand holdable scientific calculator, that sold for $395. When it became a hit, it proved the market for scientific devices affordable only by laboratories and companies.

British entrepreneur Clive Sinclair saw this as a challenge to be met. To create the first affordable scientific calclulator, he spent time in a Texas hotel room with mathematician Nigel Searle PhD, writing code containing 320 instructions for the Sinclair Scientific. When it launched in 1974, the Scientific cost £49.95 and sold as a kit. Two years later, it sold as one piece for £7.

Competition and improved programming both served to dramatically reduce the cost of such devices.

In the 1970s, Jack took an interest in using silicon technology in solar power generation technology. He also moved into education, becoming a professor of electrical engineering at Texas A&M University, between 1978 and 1984, although he officially retired from work in 1983.

As sometimes happens with groundbreaking inventions, Jack Kilby was not the only inventor of the Integrated Circuit. Robert Noyce, of Fairchild Semiconductor Corporation also worked on a design for an integrated circuit. His product was a little later and more complex than Kilby’s but a 1960s lawsuit awarded the patent to Kilby. The method of integrating the wiring into the actual circuit, ‘evaporating’, was credited to Noyce and he took that patent.

Jack won many awards for his work, including the National medal of Science in 1969, the Charles Stark Draper medal in 1989 and the National Medal of Technology in 1990.

In 2000, Jack Kilby and Robert Noyce would both be awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for the invention of the Integrated Circuit. The prize was shared at Kilby’s suggestion with Noyce, who by this time had passed away. His was an unusual award, because he was cited for his work as an applied not a theoretical physicist.

Only five years later, Jack Kilby succumbed to non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma at home in Texas, surrounded by his family. Each year, Texas Instruments still celebrates September 12, the day Jack unveiled the Integrated Circuit.

---------------------------------------------------

How far have we come in improving Kilby’s original design for what we now call the microchip?

What are the prospects for replacing the microchip with something better?

---------------------------------------------------

By Stephen Phillips Content Producer at the IET, with passions for history, engineering, tech and the sciences.