Building carbon out of the built environment requires a huge shift in culture and perspective. But, like so much else, it is an engineering problem with an engineering answer.

Buildings don’t immediately spring to mind when we think of the carbon in our atmosphere. They may not have engines, but the structures that make our built environment create vast volumes of carbon.

Achieving net-zero carbon will be very difficult without including the built environment in our calculations. Net-zero is the idea any or all greenhouse gases (GHG) emitted during the activities of an organisation should be balanced by removing a similar volume of carbon from the atmosphere. It is a huge challenge, yet if we are to avoid the worst effects of climate change, achieving net zero will be vital.

Construction is one industry where meeting such targets is especially important. Globally, 39 per cent of carbon emissions are associated with the industry, according to the World Green Buildings Council.

There are two measures of the carbon produced by the built environment.

Operational carbon is 28% of carbon emissions. This is associated with energy used in operational use – heating, cooling, and lighting - during its life.

Embodied carbon is carbon emissions associated with materials and building processes during the construction and refurbishment of buildings and infrastructure. Embodied carbon in the built environment accounts for about 11% of total global emissions.

To make construction ‘net zero’ would require an enormous shift in how the entire industry works. Yet, construction as an industry, is somewhat conservative and slow moving compared to other areas of endeavour.

Embodied Carbon Reduction – Build nothing or build less

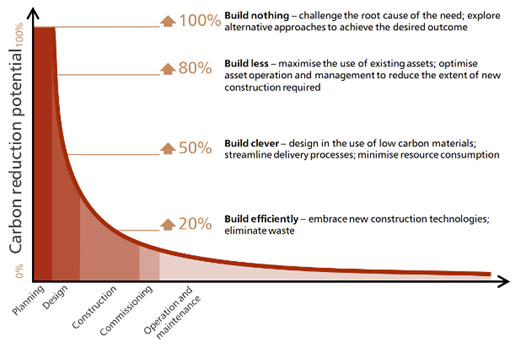

In the ‘Infrastructure Carbon Review’ of 2013, examining methods to reduce embodied carbon in buildings, the Treasury underlined four markers:

- To Build Nothing - to interrogate the necessity of building at all, and examining the alternatives.

- Build less – to repurpose and refurbish the current building stock, wherever possible.

- Build clever– to reducing the use of resources to the minimum, use low-carbon materials wherever possible.

- Build efficiently – remove waste at every level and take up new construction methods and technologies.

(Strategies for eliminating embodied carbon – Infrastructure Carbon Review, HM Treasury 2013)

Free from the clutches of carbon

One way of reducing embodied carbon, is to reduce demand for new build. When buildings *are* constructed and used, they should be done so efficiently and intelligently.

To tackle operational carbon, we must remove both direct and indirect emissions. The UK’s energy demand peaks in the winter, six times the electricity demand of the summer.

Electrifying heat is one approach. The UK grid’s carbon intensity should hit net-zero by the mid-2030s. The weight of demand for winter heating means we cannot electrify everything. Instead, we must reduce the energy demand of buildings.

To do this we can cut consumption by encouraging changes in behaviour and using energy more efficiently. We can improve the efficiency of the building envelope to reduce losses and by improving ventilation control.

Another point of attack is to decarbonise the energy supplied to buildings by using net-zero electricity, which means more renewables, better storage and local power-sharing. Similarly, we can use net-zero heat. This means more electrification, heat networks and employing ‘blue’ and ‘green’ hydrogen.

What a waste

In doing this, we must also reduce the estimated £11 billion of waste the industry generates each year. Similarly, the we must reduce the 3.5 million tonnes of CO2 the industry emits annually. That is, reducing waste in the production process for materials, waste in on-site processes, waste in the operation of buildings and at the end of life of buildings.

Nearly 5 million tonnes of non-hazardous construction and demolition waste in the UK went to landfill in 2016, while the sector has now targeted zero avoidable waste.

To reduce operational carbon, we also need to reduce energy waste, improve the performance of buildings, lower energy use in the production of materials and built assets themselves.

There are barriers to waste reduction. A lack of understanding of embodied carbon generally, and the motivation and opportunity to reduce it. There is a confusion in how to best measure carbon, with multiplpe initiatives and a labyrinthine regulatory and standards regime adding to the problem.

There needs to be better understanding of end-of-life buildings waste control as a concept. And better information about building components, what and where they are.

Reuse, reuse, reuse

The ultimate idea in reducing waste in the economy is the concept of circularity, or the circular economy.

The UN Environment Programme posits circularity, together with sustainable consumption and production, as being central to delivering on multilateral agreements such as the Sustainable Development Goals, the Paris Agreement and the post-2020 global biodiversity framework.

To take one tenet of the circular economy; the requirement to ‘circulate’ products and materials at their highest value. This keeps materials in use as a product or, when that can no longer be used, as components or raw materials. In this way, nothing becomes waste, and the value of products and materials recycled in this way is retained.

An obstacle to this is a commercial preference for building new, using new materials and on new sites. There is little interest in reusing materials because they is cheaper and lower risk to use new ones.

There needs to be better information on the products in built assets, so people know what is there to be reused.

What is in the supply chain?

Greater supply chain transparency is another necessity; to share information rather than withhold it. It needs to be more commercially attractive to reuse products and materials in the industry, a vibrant market in reused products and materials has to be established and grown.

Building without carbon

Nevertheless, there is a lot of work going into making construction more environmentally friendly.

The idea of a net zero building appears relatively simple at first, a structure that generates as few emissions as possible during construction and operation. Any future GHG emissions are offset by the developer or eventual owner.. Yet scratching below the surface to define what ‘net zero buildings’ are, and what makes something carbon neutral, becomes very complicated.

There are different types and levels of carbon net-zero buildings, and they can be hard to define, but we know them when we see them.

Similarly, different kinds of net zero buildings will have very different features depending on their purpose, but all are highly performant when it comes to energy usage. A net zero residential flat might achieve this ‘fitness’ by being extremely well insulated, whereas a big office park might achieve net zero by packing the roofs with solar panels to generate energy onsite.

There is no single model for building something in a ‘net zero’ way, and this makes it difficult for architects and construction firms to know exactly how to proceed.

The measure of carbon

The second complication is the way a building’s carbon emissions can be divided into two parts. As we have seen, there are embodied emissions (those associated with production of bricks and mortar, transportion to site, energy used in digging foundations and to eventually raise the structure). Next are the operational carbon emissions, all the energy used throughout the building’s lifespan to keep it heated, cooled, and lit up. Calculating the true carbon emissions involved in each of these instances is extremely complex.

It is currently (comparatively) easier to arrive at operational carbon costs. In the UK, as elsewhere, buildings are given an Energy Performance Certificate (EPC), which designers are obliged to produce to show the efficiency of their energy usage.

Architects will use different thermal equations in calculating the energy performance, The sticking point is that this energy rating is based on a ‘standard’ user’s energy consumption. Because there is no such thing as a standard person, some people will use more energy than is predicted by the EPC.

Then there is the issue of calculating embodied carbon in a building. This refers to all emissions associated with extraction, manufacturing, and shipping of materials to a building site. For now, there is no obligation to calculate these emissions, while working them out is made more complex by the global nature of supply chains.

Despite these difficulties, there are efforts within the industry to make ‘net zero’ construction more realistic, feasible and practicable for the widest variety of builders.

Standards and benchmarks

Tom Wigg is an advisor at industry body the UK Green Building Council (UKGBC). He says his organisation has worked with many expert bodies to build the UK’s first net zero carbon building standard, a technical update and period of consultation for this was launched in June 2023 (other partners are: BBP, BRE, the Carbon Trust, CIBSE, IStructE, LETI, RIBA and RICS).

Wigg says conceptual work has been ongoing for number of years involving several researchers and institutions. The aim of the project “is not to reinvent the wheel”, but to to pull together existing measures and guidance into a unified whole. Any builder can measure their plans against the newly cohering framework to gauge the net zero compliance of their plans and prove it to customers. The idea is to make so-called ‘greenwashing’ more difficult.

Operationally, the new standard will go far further than the current EPCs. It will demand rigourous methods and calculation of carbon emissions at initial design, at practical completion, and another measurement of emissions once the building is in use. This can provide a truer, more consistent measure of a building’s energy emissions, better than the estimates of the EPC.

The standard will also spotlight the embodied carbon in buildings. Wigg points out that growing number of construction materials now carry an EPD (environmental product declaration). This quantifies the greenhouse gas emissions associated with their production (although EPD’s are not available for most products yet).

Hope for the future

The hope is that any specified material will carry a tough EPD, particularly relating to the materials and products that have arrived on site and that it will list the product’s emissions. For now, this is more hope than expectation; most building materials are not supplied with this information. Still, there are methods of gauging these figures.

It can be hoped that arriving at a measure of embodied and operational emissions will become easier in the future using software. Using Building Information Modelling (BIM) technology to create interactive digital blueprints could make these calculations in parallel to the designer drawing up a building’s plans. This type of software could feasibly show the volume of emissions generated by different designs and materials, and make it easier to develop environmentally friendly structures.

How do we reduce the carbon in buildings?

Do we need more and better technology? Or is this a case of going ‘back to the future’, to employ the materials we used to use in our buildings, before the Industrial Revolution?

And how do we more accurately measure the carbon that goes into and comes out of a building, over its lifespan?

It’s always worth engaging with colleagues and fellow engineers, so why not throw in your thoughts in the comments right now? If you’re not an EngX member you can sign up to EngX here. If you are, log in and jump straight in!