On this day in (engineering) history…

February 13, 1867 - Work begins on covering Brussels’ River Senne

Picture this, on a cold February morning (the 13th in fact), in 1867 you’re standing on the muddy bank of the River Senne, the main river running through the heart of Brussels, Belgium. It is revolting to the senses. The depleted, slow-moving river is polluted with rubbish thrown into the waterway, industrial effluent and raw human sewage. The smell is overpowering. The river often floods and carries this toxic mix into the homes of residents in the city’s nearby working-class areas. Clearly, something must be done, but what? Well, today, the city begins to bury the river.

Like many rivers flowing through the heart of Europe’s cities cities in Europe, the River Senne (as opposed to the Seine in Paris) had for centuries been a dumping ground for all manner of waste and rubbish.

When the weather was dry, water would be diverted from the river to supply the populace, and to maintain the levels of the many canals that had replaced it as a navigable channel. During heavy rainfall, the flow became uncontrollable overpowering the city’s sluice gates and flooding the lower town.

As the population increased, so the need for space fueled encroachment onto the riverbed, narrowing the channel. Added to this were the many support arches of multiple irregular bridges with accumulating waste and sediment on the riverbed combining to raise the level of the water.

These dry periods, poverty and overcrowding, plus a cholera epidemic pushed the city to Do Something. Schemes to clean and purify the Senne were deemed unfeasible. Other designed proposed diverting the river. Still others suggested simply covering it and widening the drainage tunnels to take an underground railway.

Things came to a head when in 1865 the city Mayor, Jules Anspach, chose a design by architect Léon Suys to remedy the situation. The design meant burying the river and placing grand boulevards and buildings on top.

Land would be expropriated and sold off after completion, as a method of financing the whole project. This land would be part of a grand boulevard and would become an upper-class area. The original residents would have to live elsewhere.

As with so many such projects, it faced fierce opposition on grounds of cost and the demolition of the areas in which ordinary people lived.

Fear of high taxes used to pay for the expensive project was one source of opposition. Another was claims by engineers that it did not suite the geology of Brussels, that covering the river would create a trap for toxic gases and the tunnels would be unable to cope with flooding. In the press, Anspach, the Mayor, was greatly criticised for demolishing the old town.

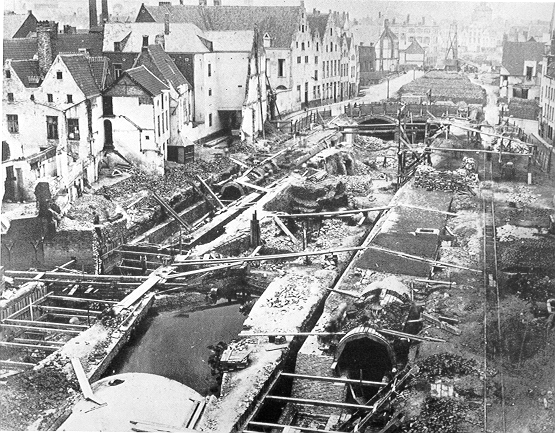

The covering of the Senne in Brussels. Wikimedia, Public Domain

A British company, the Belgian Public Works Company, was given the task of seeing the project through. An embezzlement scandal involving 2.5million Belgian francs put that to rest in 1869. Anspach barely survived that year’s city elections.

Being built of brick, the cover would consist of two 6-metre-wide parallel tunnels extending for 2.2 kilometres. Two lateral drainage pipes would take wastewater from either side of the street. New boulevards - what are now the Boulevard Maurice Lemonnier/Maurice Lemonnierlaan, the Boulevard Anspach/Anspachlaan, the Boulevard Adolphe Max/Adolphe Maxlaan, and the Boulevard Émile Jacqmain/Émile Jacqmainlaan - were all set out between 1869 and 1871 and opened to traffic after 1871. The first stone was laid by King Leopold II himself.

The city would look very different after the completion of the covering.

Postscript: There are ongoing plans to partly uncover the Senne – ‘partly’ because there is now serious infrastructure, such as the city’s main railways station, built above the old river. The first stretch involved removing nearly 2000 tonnes of concrete from a 200-metre length of the Senne near the suburb of Buda, in the north of the city. Much of that rubble was used to rebuild the riverbank.

It could be said the toughest problem to overcome has been the feeling of Brussels residents (known as Bruxellois) toward their river. The Senne has been a sewer for so long no attempt to clean the water was made until 2000. In 2010, the river was listed as ‘dead.’ Purification attempts bore fruit when fish were found in large numbers in 2016. Work has been ongoing since 2023 at Maximilien Park, in the city centre, to uncover more of the Senne. This is expected to be completed in 2025.

As we have seen, there is major infrastructure blocking the re-opening of the whole river, the Senne is in far better condition today than it was. While the entire length cannot be un-buried, perhaps something is better than nothing.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

How far is it possible to replicate or preserve nature and natural environments within such an artificial environment as a city?

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Stephen Phillips is an IET Content Producer, with passions for history, engineering, tech and the sciences.

-

THAYALAN GANESHAN

-

Cancel

-

Vote Up

0

Vote Down

-

-

Sign in to reply

-

More

-

Cancel

Comment-

THAYALAN GANESHAN

-

Cancel

-

Vote Up

0

Vote Down

-

-

Sign in to reply

-

More

-

Cancel

Children