On This Day in (Engineering) History

If you want to share a thought or some information you write it in a letter, put that in an envelope and slip it into a post box in the street. Anything bigger, like a box of files or a book, is sent as a parcel carried by couriers, and it all – letter or parcel - travels through a postal system made up of thousands of people delivering everything by hand.

Not anymore. On April 30, 1993 - CERN announces that World Wide Web protocols will be free to all.

Just to be aware…

To clear up a common misunderstanding, one that has entered the language – the World Wide Web (WWW) is not the Internet.

The internet - how we got here

Like the invention of the wheel, the sail, the motorcar and the coffeemaker, it is hard to imagine how life was before the World Wide Web was launched. No-one under 30 will remember writing a letter, posting it and waiting days or weeks for a response. Or having to go shopping, at bricks and mortar buildings because there is no online in which to order stuff.

Visualization of Internet routing paths Source: The Opte Project via Wikimedia Commons

The seeds of what we now call The Internet, began with Leonard Kleinrock and his paper "Information Flow in Large Communication Nets" of 1961.

In the early 1960s, JCR Licklider, director of the Information Processing Techniques Office, within the Department of Defense, proposed a network of linked computers. Independently, Paul Baran, over at the RAND Corporation, proposed a distributed network using message blocks. Across the pond, at the UK’s National Physical Laboratory, in Middlesex, Donald Davies came up with packet switching, suggesting a commercial network link between the US and UK.

In 1969, the US Department of Defense’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) awarded the contracts to build ARPANET, the forerunner of what we now call the Internet. By the way, first person who used the term ‘the internet’ in writing, is usually held to be US computer scientist Vint Cerf in 1973.

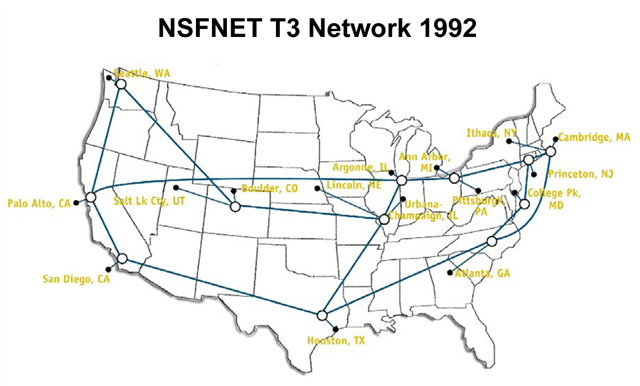

Staying with the US, the National Science Foundation funded the creation of supercomputing centres across the US, which were linked by…NSFNET, a network that had over 2 million connections by 1993.

NSFNET Backbone, c. 1992 Source: Wikimedia Commons

What they lacked was a common, simple to use method of linking data held at different locations and making it easily accessible to anyone that needs it.

The difficulty of finding stuff out…enter CERN and Tim Berners-Lee

CERN from the air Source: Wikimedia Commons

It may be a generational memory thing, but back in the day, finding and retrieving information on different computers could be time consuming and arduous. At least in a library the books can be physically carried to a table or a desk to check through. Not so with the computers of the time.

This is where the Conseil Européen pour la Recherche Nucléaire, better known as CERN, comes in. Or rather Tim Berners-Lee, a computer scientist working for the European physics laboratory based on the Franco-Swiss border, high in the Alps, near Geneva.

Sir Tim Berners-Lee was born in 1955, (he was knighted in 2004). His parents were mathematicians who worked on the Ferranti Mark 1, the world’s first commercial computer. During his childhood he built make mock-up computers from cardboard boxes, and fell in love with trains and model train sets, which kicked off his interest in electronics. Perhaps his father’s influence can be seen when we learn that Berners-Lee senior worked on ideas around the human brain, and linking computers into a network.

TimBL (as he is also known) studied physics at Queen’s College, Oxford, where he built a computer from old television parts, a calculator, an old car battery and an electrical kit.

Tim Berners-Lee in 2005 Source: Wikimedia Commons

The moment

Fast forward to March 1989 – he was a research fellow at CERN, which was then the largest internet hotspot in Europe. Berners-Lee pitched a paper suggesting a method of linking information, writing, “‘web’ of notes with links (like references) between them is far more useful than a fixed hierarchical system.” His manager described the paper as ‘vague, but exciting.’ And didn’t stop him continuing his work.

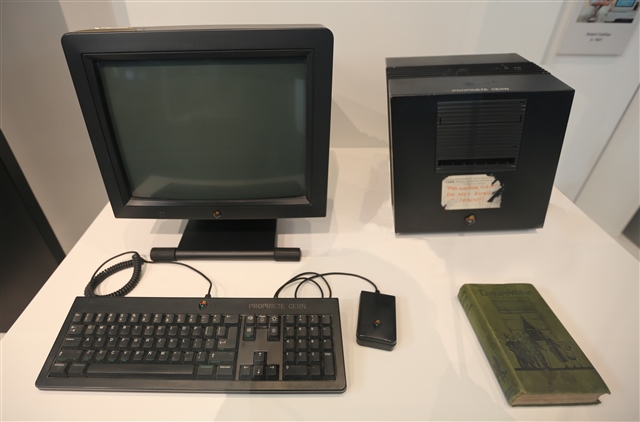

A second paper appeared in May 1990, which was worked into a management proposal (with Belgian systems engineer Robert Cailliau) in November that year. Before the year was out, Berners-Lee’s own NeXT personal computer (or PC) was equipped with a web browser and had become the very first webserver. Permanently switched on, it was marked with a handwritten label, "This machine is a server. DO NOT POWER IT DOWN!!" As we can see, it was written in red ink.

The NeXT Computer used by Tim Berners-Lee at CERN became the first Web server Source: Wikimedia Commons

By this time Berners-Lee had already created three fundamentals of the Web:

- Uniform Resource Identifier (URI) – the address identifying the source, location and properties of a resource on the Web.

- HyperText Markup Language (HTML) - the computer language that structures, orders and presents everything you see on the page. It also organises tags and labels to create the links we see on the site.

- Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) – the protocols that describe and organise the location and characteristics of an online information source, how it links to other sources and how it is delivered to the user.

Among the things he thought of doing was using alternative names such as ‘Information Mesh’, ‘Mine of Information’ or ‘Information Mine.’ World Wide Web stuck.

The memo

This revolutionary new technology was released from CERN, to the world at large by Walter Hoogland (then Director of Research), and Helmut Weber, (then Director of Administration) in an internal letter.

The key paragraph was:

“CERN relinquishes all intellectual property rights to this code, both source and binary form, and permission is granted for anyone to use, duplicate, modify and redistribute it.”

In 1994, this release became an ‘open source release’, not a ‘public domain release’, a technical detail which allowed CERN to retain copyright, while still allowing anyone to do with it what they wished.

The World Wide Web was not the only method of distributing information in this way. A rival team at the University of Minnesota had created Gopher, to do the same job, albeit in a different way. Simpler, perhaps easier to use and…first. But the University decided it should charge commercial Gopher users hundreds or thousands of dollars for a license. Gopher never recovered.

The fact that I am writing this, you are reading it (I hope) in the way we are – and that it is not considered strange - is a testament to the strength of the ideas and vision of both Tim Berners-Lee (the WWW concept and software) and CERN. Few people can claim to have changed the world to the same degree.

Given the extent of the change the WWW has made possible, to what extent is it possible to imagine and build something better, more efficient and easier to use than the WWW? Share your thoughts in the comments!

By Stephen Phillips - IET Content Producer, with passions for history, engineering, tech and the sciences.

By Stephen Phillips - IET Content Producer, with passions for history, engineering, tech and the sciences.