On this day in (engineering) history…

February 25, 1836 - Samuel Colt Patents the Colt Paterson Revolver

"There is nothing that cannot be produced by machinery." – Samuel Colt, 1854

When a new machine or device is patented, it has the potential to save life, add to life or take it. Or, by allowing people to protect themselves, save life. Either way, Samuel Colt's Paterson Revolver will change handguns forever.

A Curious Child

Samuel Colt was born in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1814. His father was a farmer turned city businessman, while his mother died of tuberculosis when Samuel was 6 years old. His three sisters would also pass away at a young age. His father eventually remarried.

Samuel Colt was born in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1814. His father was a farmer turned city businessman, while his mother died of tuberculosis when Samuel was 6 years old. His three sisters would also pass away at a young age. His father eventually remarried.

When Samuel was eleven, his father indentured him to a farmer from Glastonbury, where he did chores and went to school. Attending school appears to have lit up his curiosity; his favourite hobby became taking things apart to see how they worked, including his father's firearms collection.

The school introduced Samuel to science and engineering with a book called Compendium of Knowledge. The Compendium changed his life with its articles on all things scientific and technological (including explosives).

Explosive interests

Working at his father's textile mill in Ware, Massachusetts, he built a galvanic cell using the knowledge he picked up in the Compendium. Later in the year, he advertised a July 4 event at Ware Pond, where he promised underwater explosions powered by his galvanic cell. While the explosions worked a treat, the raft he intended to sink moved on the water, so it survived its intended sacrifice.

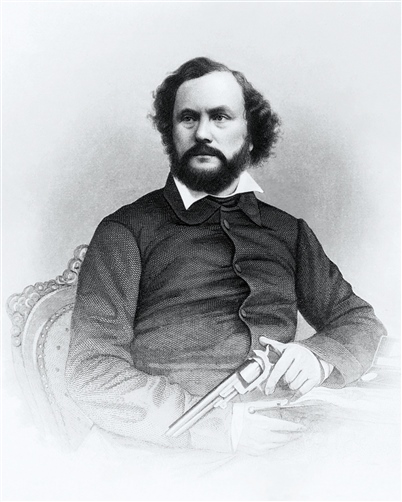

Samuel's father sent him to a boarding school, where an accident on July 4 burned down a building, for which the school expelled him. At this moment, the story of the Colt pistol properly takes flight because his father put him to sea in another attempt to make something of him. Samuel Colt Source: Wikimedia Commons

His ship, the Corvo, was heading for the Indian port of Calcutta. By the time the Corvo arrived in India, the ship's steering mechanism, especially the ship's wheel, had caught Samuel's attention. It could be turned or spun and locked in place by a clutch. Perhaps he could use this in a far smaller instrument than a ship's steering - such as a pistol with a revolving chamber to hold enough ammunition for six shots without reloading.

Samuel developed the idea in a prototype featuring a six-barrel cylinder, locking pin and hammer, all carved in wood. The multi-barrel cylinder did not last. He dropped the idea in favour of a multi-chamber cylinder to reduce weight and make the pistol easier to use.

Patently Obvious

Initially, that cylinder had to be hand-aligned with the barrel, which was potentially dangerous if there was even a slight misalignment. Features such as a cylinder lock, bevelled cylinder mouths, fluted cylinders, and a longer grip appeared later, each protected by a separate patent.

A patent office in London issued Samuel's first patent for his new revolver (No. 6909) in 1835. More significantly, the US Patent Office issued his first US patent (US Patent 9430X) on February 26, 1836, with a second (US patent 1,304) dated August 29. These protected the basic design of the Colt Paterson, including features such as the revolving chamber, breach loading, and folding trigger. Significantly, the patents were in the name of Samuel Colt, not a company.

A patent office in London issued Samuel's first patent for his new revolver (No. 6909) in 1835. More significantly, the US Patent Office issued his first US patent (US Patent 9430X) on February 26, 1836, with a second (US patent 1,304) dated August 29. These protected the basic design of the Colt Paterson, including features such as the revolving chamber, breach loading, and folding trigger. Significantly, the patents were in the name of Samuel Colt, not a company.

The Patent Arms Manufacturing Company, based in Paterson, New Jersey, would follow on March 5, 1836, the day the state of New Jersey chartered it. (Img: Colt Paterson No.5)

Misfires

A founding idea was that Colt would make his firearms with interchangeable parts on one of the earliest production lines.

"The first workman would receive two or three of the most important parts and would affix these and pass them on to the next who would add a part and pass the growing article on to another who would do the same, and so on until the complete arm is put together."

The new system had its teething troubles. Production was slow, and quality control was uneven. Using interchangeable parts was a new idea, and reproducing to standard across several factories proved beyond Samuel and his colleagues. As a result, sales (primarily to the US Government and the States) were slow.

In 1843, the Seminole War appeared to give the Paterson factory a lifeline, only for the deal to fall through when the pistols and rifles proved too far ahead of their time. The weapons were so unusual that soldiers took them apart, breaking some parts. Payment for the guns was not forthcoming, and the result was the closure of the Paterson facility the same year.

Revolution in Industry

Until the second quarter of the 19th Century, artisan gunsmiths lovingly handcrafted every musket and other firearms, making each weapon a unique piece. It would take a master blacksmith to repair and maintain them in the field. The whole process was expensive and (above all) highly inefficient. After 1811, there were attempts to streamline the production of weapons.

In 1849, Samuel built a new factory in Hartford, Connecticut, partly (it has been claimed) to lure one Elisha K. Root from the Samuel W. Collins Company (where he was making axes) into joining Colt as the Superintendent of the new facility. Root had revolutionised the production of axes, altering the process to make it ever faster and more efficient. The key was using machine tools, one of Root's key skills.

All Colt pistols consisted of a set of interchangeable parts, each made in a precision mould. The life of these parts began as a raw, blank metal piece. They would be precisely held in place by a jig in a cutting machine before being worked on by specially made machine tools - lathes, drill presses and milling machines. Next, inspectors armed with gauges and callipers measured the newly fashioned pieces against exacting specifications. What began as a blank piece of iron or steel would become 'just another' precisely made part for a Colt gun. Colt was among the first to make a product using production line techniques on a truly mass scale.

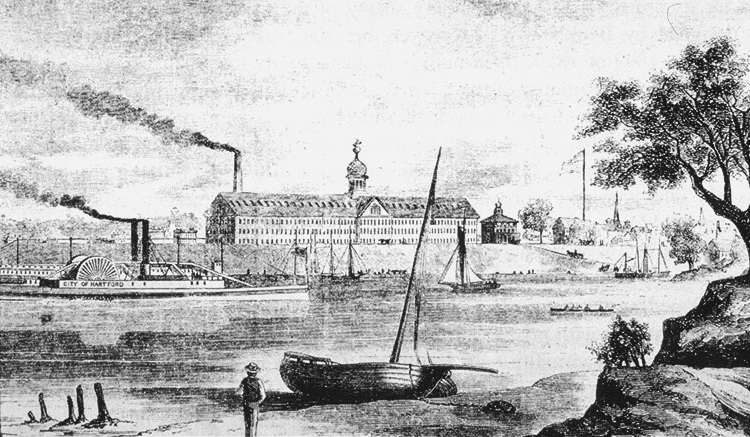

The armoury at Hartford, Connecticut, viewed from the east. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The armoury at Hartford, Connecticut, viewed from the east. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Elisha Root became known as New England's finest mechanic. He would share his knowledge and skills with his workforce, who would go on to build and operate specialist machine tools and run the production operation. Ambitious mechanics flocked from across the northeast US to work at Samuel's Hartford factory. When they left to take up other jobs at engineering companies, these workers could apply the skills involved in forging, milling, grinding and pressing to make any industrial product. So much so it became known as a 'college of mechanics.' Sewing machines, bicycles and car components all used the skills and techniques developed at Colt's Hartford factory – the world's largest private armoury by 1855.

Changing Borders, Changing Fortunes

For twenty years, Samuel struggled to make his business successful. After the Paterson plant's closure, Samuel spent several years on other projects. He teamed up with Samuel Morse to design a waterproof covering for telegraph cables, allowing them to go undersea, through lakes and rivers. He produced underwater mines (something the US War Department saw as un-Christian and dishonourable) to use as harbour defences and firearms cartridges made from tin foil instead of paper. None of these had the promise of the revolver.

As a would-be arms manufacturer, the US determination to expand its borders south and westwards was a stroke of luck for Samuel.

Just as war kicked off between the US and Mexico, Captain Samuel H. Walker of the Texas Rangers visited Samuel Colt with a view to ordering some pistols, but with the proviso that Samuel would enhance them to the Captain's requirements. Walker asked for six shots instead of five, faster reloading and more power to kill targets with a single shot.

With the changes made, the result was the Colt Walker, of which Walker ordered a thousand, then another thousand. With no way of producing his own weapons, Samuel engaged another manufacturer, Eli Whitney Blake, to make the guns. A profit of $10 per pistol allowed Samuel to purchase Blake's machine tools and set up the new factory in Hartford, Connecticut.

Even better for business was the outbreak of the US Civil War. Just as he had done in other parts of the world, Samuel sold weapons to both sides, for which he was called a traitor to the Union. Although, this was before the introduction of trade restrictions on the Rebels.

The End and a Legacy

By now, Samuel's health was failing. He died at the age of 47 (young, even by the standards of the day) from gout. In the 25 years he was active in manufacturing, Samuel's companies produced 400,000 revolvers. The work of Samuel and others at the Hartford armoury, the 'mechanics college,' turned the city into a centre of industrial innovation. This US chapter of the Industrial Revolution, the rapid growth of industrial production powered by machine tools, would be a key anchor of US power in the 20th Century.

In his lifetime, Samuel opened libraries and educational courses for his workers, engineers, toolmakers, and machinists. They nurtured several generations of engineers, including Francis A. Pratt and Amos Whitney, founders of Pratt & Whitney.

Pistols such as the Colt Paterson, the Colt Walker, the Colt Navy Revolver and (much later) the M1911 would (rightly or wrongly) become icons of US expansion in the old west, the frontier and urban organised crime.– all a result of Samuel's genius for manufacturing as well as salesmanship and the kind of advertising (art, corporate gifts and product placement) we take for granted today, which itself is another story.

Share your thoughts!

How vital has arms manufacturing been to engineering and technology in the last two hundred years, and could we have done without it? Share your thoughts in the comments below!

By Stephen Phillips - IET Content Producer, with passions for history, engineering, tech and the sciences.

By Stephen Phillips - IET Content Producer, with passions for history, engineering, tech and the sciences.