On this day in (engineering) history…

June 4, 1910 - Christopher Cockerell, English engineer, invented the hovercraft (d. 1999)

On Saturday, June 4, in the summer of 1910, anyone standing outside ‘Wayside’, a house on Cavendish Avenue, in the university city of Cambridge, would have noticed the comings and goings of a birth in the family that lived there - midwife, a doctor, family members.

The Cockerell family who lived at Wayside were famous already, their newborn son, Christopher would make them even more famous by inventing the hovercraft.

Sir Christopher Cockerell in 1976 Source: Wikimedia Commons

Famous father and his famous friends

Christopher’s father, Sir Sydney Cockerell was a typographer and Director of Cambridge’s Fitzwilliam Museum. Before that, he had been secretary to William Morris, a leading light of the Arts and Crafts movement. Among Sir Sydney’s friends were John Ruskin, George Bernard Shaw, Thomas Hardy and T.E. Lawrence. His mother, Florence Kingsford Cockerell was a designer and illustrator.

Despite his family’s firm affinity with the arts, these famous friends bored Christopher. Instead, his curiosity was caught by thoughts of steam trains and crystal sets. Among his early projects, he built a steam engine to power his mother’s sewing machine, something she ignored, preferring to power it by hand.

Dreams of technology

When he reached 17 years old, he went off to Peterhouse College, Cambridge, to study engineering. He appears to have spent much of his time dismantling, rebuilding and racing motorcycles, something which led his father to claim his son was "no better than a garage hand." Sir Sydney did support his son, though, paying for Christopher’s early patents. Christopher later said the motorbikes taught him basic engineering, what would (or would not) work and why.

He graduated in 1931 and spent the next few years working for an engineering firm before returning to Cambridge to research electrical engineering. He only hit his stride after abandoning his research (he felt ignored because he was young) and joining Marconi, where, for a salary of £250 a year, he worked on equipment for use in early television broadcasting.

The Second World War changed his direction to leading the team that developed the radio direction finder. Starting work in October 1939, it was installed in British aircraft four months later. As the war progressed, Christopher developed equipment to locate German radar stations on the European coast, which were later bombed in preparation for the Normandy Landings. Memories of D-Day pushed him to think about how to rapidly land troops on a beach and keep them dry. By war’s end, he had picked up 36 patents, for which the reward was £10 apiece.

A hard-to-starboard turn

Christopher quit Marconi in 1951 and…bought a boat and caravan hire business in Norfolk. This eventually got him thinking about moving a boat over water at high speed. It struck him that if the boat is wholly lifted out of the water, it can be made to run at speeds far in excess of regular shipping. But how?

Let’s rewind for a moment, back to the 19th century. Engineer and torpedo boat inventor, Sir John Thornycroft hypothesised that a boat could be raised out of the water by pumping air into a concave space between the boat bottom and the water surface. He had noticed something aircraft pilots would spot in later years, the ‘Ground Effect’ - a build-up of air-pressure between the wing and the ground that creates something like a funnel for the plane to ‘float’ on.

Thornycroft’s main problem was how to contain the air cushion between boat-bottom and water-surface? This conundrum was never solved, until…

The Lyon and the Kit-e-Kat

Sir Christopher Cockerell's workshop reassembled at Lowestoft Maritime Museum Source: Wikimedia Commons

Christopher took an interest in how a Lyons coffee tin, an empty tin of Kit-e-Kat cat food connected to a vacuum cleaner motor could raise an object, off the ground. The kit-e-kat tin was placed inside the coffee tin to make a snug, but not too snug, fit. Air was forced through a hole at the top of the coffee can, so it exited through the gap between the tins. The first test was to use the contraption to move the pan of a weighing scale, weighed with weights. Blowing air through one tin barely moved the scale, blowing air through the nestled tins created an annular jet, which moved the scale.

By 1955 a boatbuilder friend had helped him build a working prototype and obtained the patent in 1956.

Getting the attention of the government proved more challenging. Legend has it that the Navy had no interest because they saw it as an aircraft not a ship. The Royal Air Force saw it as a ship, not an aircraft and the Army ignored it. Whitehall listed the invention ‘Secret,’ which prevented Christopher from discussing it or making any real progress with it.

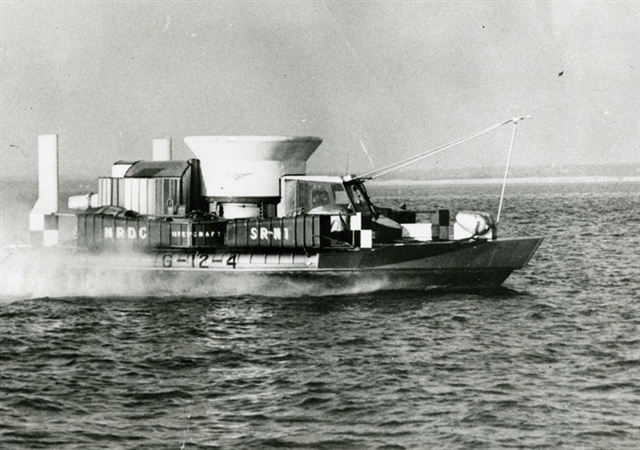

The National Research Development Corporation (NRDC) later invested £1000 to further develop what Christopher now called the ‘hovercraft.’ The boatbuilder Saunders-Roe designed and built the SR-N1 (Saunders-Roe – Nautical 1), launched on June 11, 1959.

Experimental Hovercraft SRN-1 during trials by the Royal Navy. Date: c.1963. Source: Wikimedia Commons

When the SR-N1 crossed the channel on July 15, it became obvious there were problems to be solved.

The main issue was the height at which the SR-N1 could clear the waves – or couldn’t. It had a ‘ground’ clearance of 38 centimetres. It was found that the new hovercraft could not clear waves more than 50 cms or obstacles greater than 24 cms high on land. The answer was one of the hovercraft’s more unique features, a wraparound rubberised fabric skirt.

These skirts were under constant development, to create something that could withstand friction with the water or land. An efficient and economic skirt didn’t appear until 1965.

In 1966, the NRDC set up Hover Development Ltd, with Christopher as both Director and Technical Advisor. It was to develop commercial hovercraft, with five private companies hired to build the resulting machines.

A Lithuanian Coast Guard Griffon Hoverwork 2000TD

hovercraft with engine off and skirt deflated...

Source: Wikimedia Commons

…With engine on and skirt inflated.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Moving on

In later life, Christopher took up other interests, although staying with the sea. In 1974, he become became Chairman of Wavepower Ltd, a British company researching the potential of generating energy from waves at sea, something he was still interested in before his death, at home in Hythe, Hampshire, in 1999 at the age of 88.

Like so many front-line engineers, Christopher Cockerell took an interest in several different areas of engineering and produced something visionary and truly out-of-the-box that still defies categorisation.

Beside international recognition, Christopher obtained 55 patents for the hovercraft, a word he coined himself. He was knighted in 1969. Of all of his achievements, he was proudest of the radio direction finder, a device that saved many lives during World War Two.

SR.N4 ‘Mountbatten’ class hovercraft arriving in Dover on its last commercial route across the English Channel (1 October 2000) Source: Wikimedia Commons

Epilogue: The fastest commercial, car carrying crossing of the English Channel took place on September 14, 1993. The SR-N4 Mk III ‘Princess Anne’ made the crossing in 32 minutes. More regularly, crossing times took 22 minutes with an average speed of 65 knots.

To what extent is it true that the best engineers work across multiple fields? How can we make better use of the hovercraft, and what else does this technology have left to give?

By Stephen Phillips - IET Content Producer, with passions for history, engineering, tech and the sciences.

By Stephen Phillips - IET Content Producer, with passions for history, engineering, tech and the sciences.

-

Deborah-Claire McKenzie

-

Cancel

-

Vote Up

0

Vote Down

-

-

Sign in to reply

-

More

-

Cancel

-

Former Staff Member

in reply to Deborah-Claire McKenzie

-

Cancel

-

Vote Up

0

Vote Down

-

-

Sign in to reply

-

More

-

Cancel

Comment-

Former Staff Member

in reply to Deborah-Claire McKenzie

-

Cancel

-

Vote Up

0

Vote Down

-

-

Sign in to reply

-

More

-

Cancel

Children