By Anne Locker, Library and Archives Manager

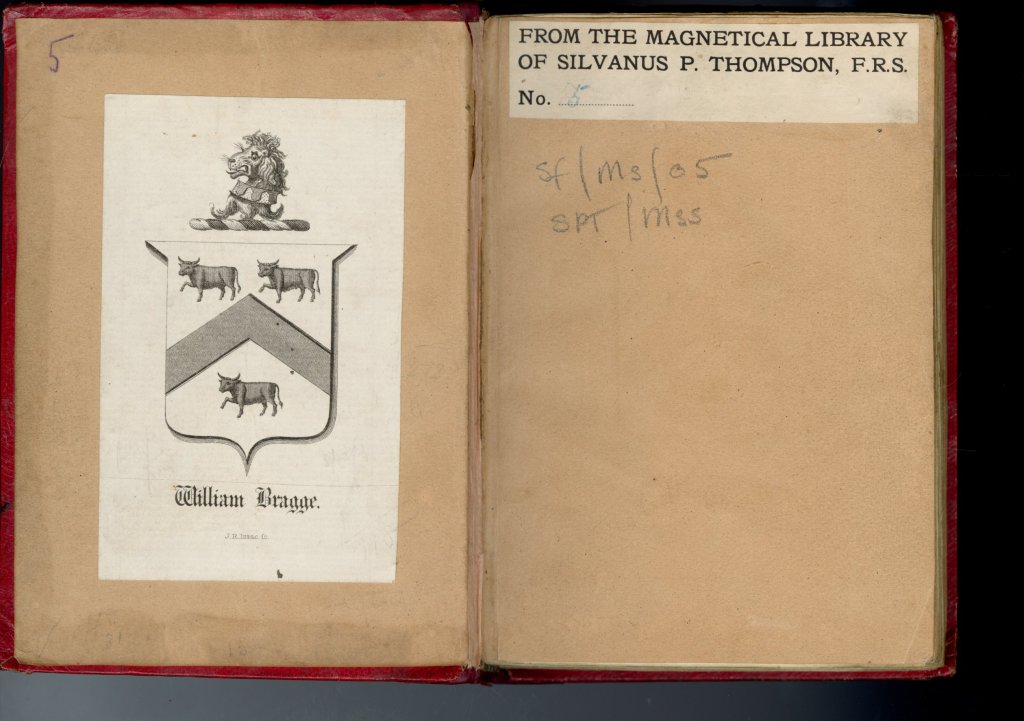

The Hand List of the Library of Magnetic and Electrical Books in the Possession of Silvanus Phillips Thompson is the earliest record we have of the S P Thompson Library, acquired by the Institution of Electrical Engineers (now the IET) after Thompson’s death in 1916. Silvanus P Thompson – engineer, polymath and bibliophile – published this meticulous record of his library of 13 manuscripts and around 900 early printed books on the history of science in 1914.

Five of the manuscripts in Thompson’s collection are dated before 1600. The smallest of these is a much earlier catalogue of scientific texts, the Speculum Astronomicae of Albertus Magnus.

The manuscript is described by Thompson as follows:

MS XIV Century. Vellum, 56 ll. + 2 blank. (3 ¾ x 5 ¼ inches.)

ALBERTUS MAGNUS. Speculum Astronomicum.

Contains also THEBITIUS, Liber Ymaginum Astronomicarum.

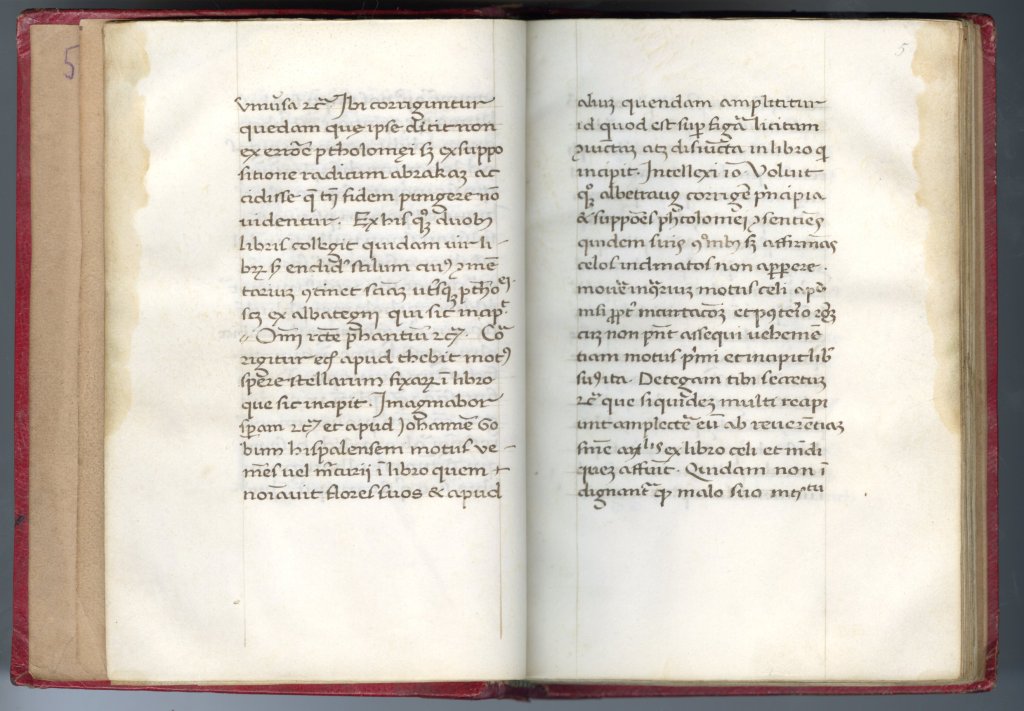

There are two works in this small manuscript, now dated to the 15th century. The first is by a 13th century German Dominican friar, scientist and philosopher, Albertus Magnus. The second is an earlier manuscript by Thabit ibn Qurra, a mathematician, scientist and court astrologer who lived in Baghdad in the 9th century.

The ‘Speculum Astronomicum’ of Albertus Magnus

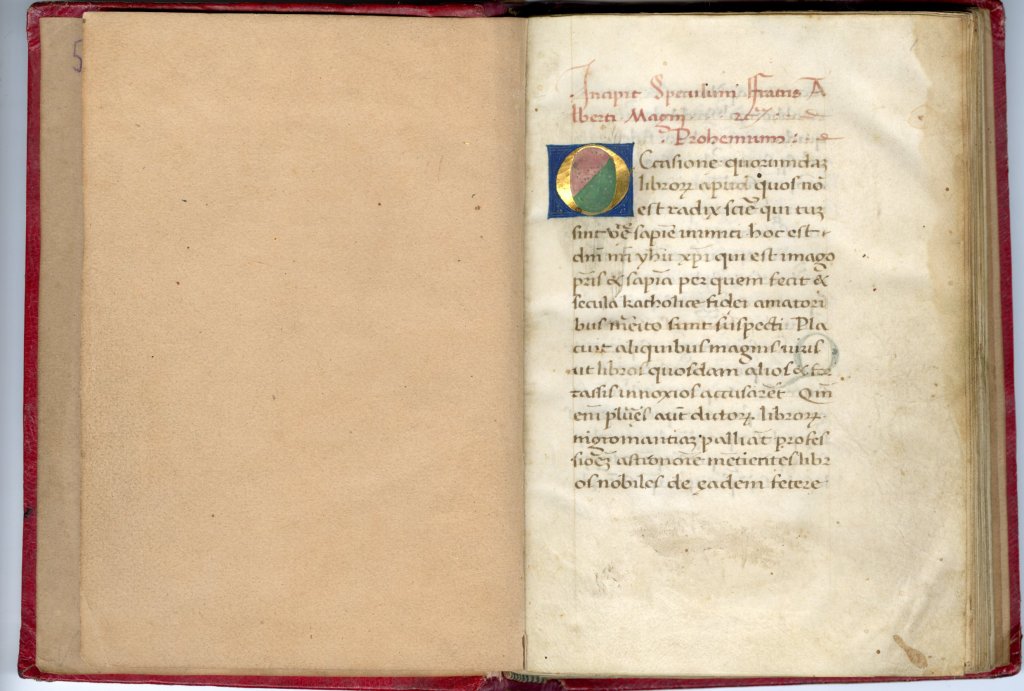

Looking at the first folio of this little manuscript, we can see that it begins with an ‘incipit’: a summary which in medieval manuscripts identifies the text (a bit like a title page). It’s often written in a different colour to the main manuscript, and here it is written in red above an illuminated capital O. It reads: ‘Incipit Speculum Tractis Alberti Magni’, or (roughly) ‘Here begins the Mirror, a treatise by Albertus Magnus. The title for the first section, ‘Probemium’ (prologue) is also in red.

We refer to this treatise today as the Speculum Astronomiae, or the ‘Mirror of Astronomy’. Although there has been some debate over its authorship, it is usually attributed (as in this manuscript) to the medieval scientist and philosopher Albertus Magnus, St Albert the Great.

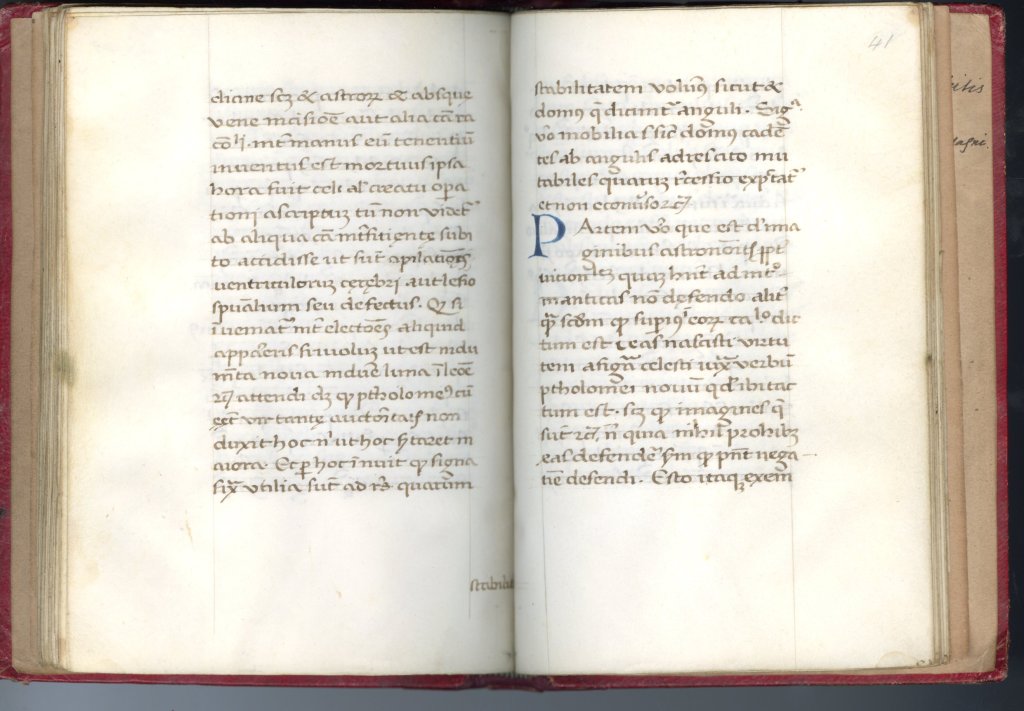

The treatise was written to respond to the Christian church’s criticism of the inclusion of ideas from Aristotle and other classical philosophers into medieval philosophy and science, and especially the condemnation of astrology as a form of witchcraft, linked to the Condemnations of 1277.

Albertus was the first person in medieval Europe to produce a commentary on the works of Aristotle. He is credited with preserving our knowledge of this philosopher’s work in the Western philosophical tradition, and centred the curriculum of the Dominican order on classical philosophy. The religious and philosophical debates of the time – and the move to condemn classical philosophy as blasphemous and idolatrous – were a high risk to him personally and to the continued existence of these texts and the ideas they explained.

The Speculum aims to remedy this with a detailed summary of Greek and Arabic texts on astronomy and astrology, dividing them into acceptable, or ‘noble’ works and illicit, or ‘necromantic’ works, the latter relating to witchcraft and being rightly (in Albertus’ view) forbidden.

Albertus wanted to show how ideas from classical astronomy and astrology could sit alongside Christian doctrine. The result is a philosophical discussion on whether astrology can be justified in theological terms, and a comprehensive list of all the Greek and Arabic texts on astronomy and astrology that were available in the 13th century.

The images in this blog are from the IET manuscript (SPT/SF/MSS/05), which was originally in the library of the civil engineer William Bragge.

Translated extracts of the Speculum are from Paola Zambelli, The Speculum Astronomiae and its Engima, which also includes a detailed commentary on the text (Zambelli, 1992). Zambelli describes the Speculum as a:

“bibliographical as well as methodological introduction to the texts and the fundamental problems of astrology.”

Zambelli, The Speculum Astronomiae and its Enigma, p. 4

It was a very useful addition to Thompson’s library, which contained other important early texts on astronomy and navigation.

The science of astrology

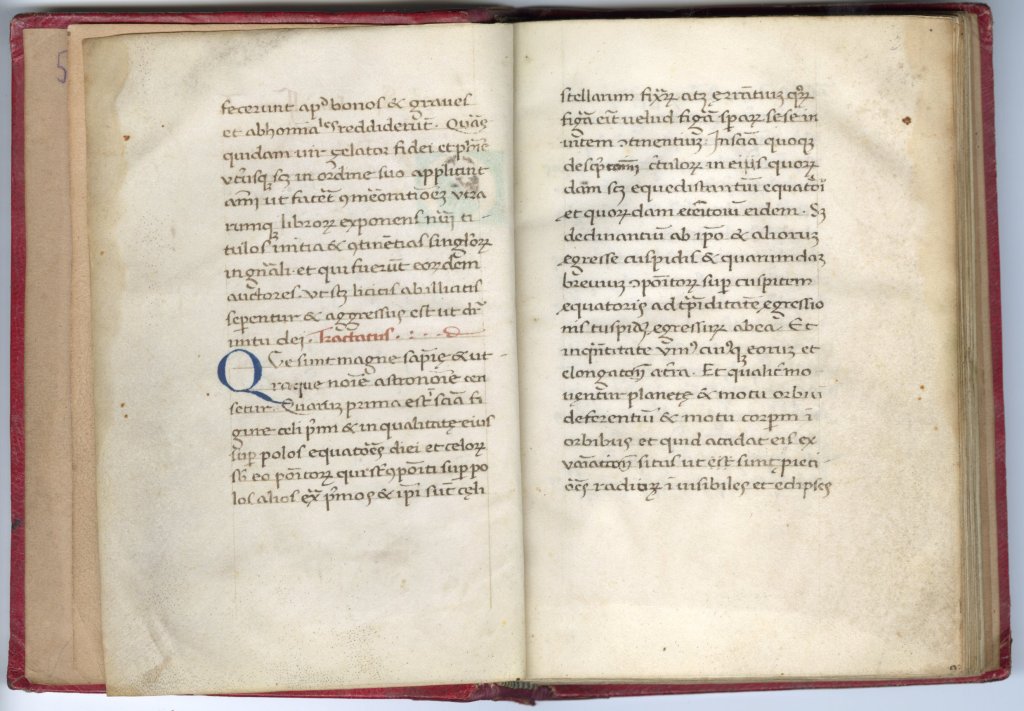

In the first section of this treatise, Albertus described astronomy as the science of the ‘fixed and wandering stars, whose configuration is like the configuration of spheres enclosing one another’ (Zambelli, p. 213).

Astronomy was based on observations and ‘cannot be contradicted, save by someone who opposes the truth’ (ibid.). Albertus argued:

“..these are the books, which if they are removed from the sight of men wanting [to study them], a great and truly noble part of philosophy will be buried at least for a certain time, that is, until it would rise again due to a sounder attitude; for, as Thebit, the son of Chora, says: ‘there is no light in geometry when astronomy has been removed’.”

Zambelli, p. 213

We will return to Thebit, son of Chora, in the second part of this manuscript.

‘The science of the judgments of the stars’

Albertus described astrology as the ‘second great wisdom’ and ‘the science of the judgments of the stars’ (Zambelli, p. 213). He saw astrology (which he also referred to as astronomy) as a tool. If the stars and celestial bodies influence people and events, Albertus argued, this reflects the Christian truth that the universe obeys the will of God.

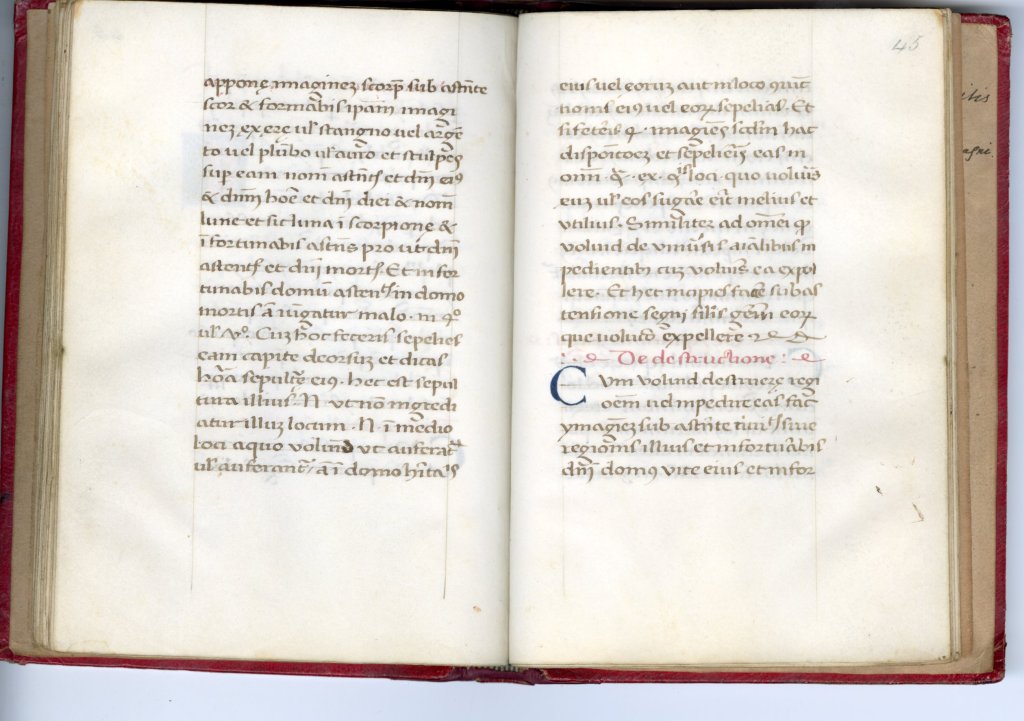

One aspect of astrology that Albertus discussed in this treatise is the use of images. He distinguished between what he called ‘necromantic’ images, which invoked evil powers and which should be condemned, and ‘astronomical’ images, which may have been misguided but were not sinful. Astronomical images, said Albertus, are a way of reflecting the powers of celestial bodies on earth.

One of the authors on astronomical images Albertus discussed (and who fell on the right side of the necromantic/astronomical divide) was Thebit, son of Chora, or Thabit ibn Qurra, the author of the second treatise in this manuscript.

Thabit ibn Qurra, Liber ymaginum astronomicarum

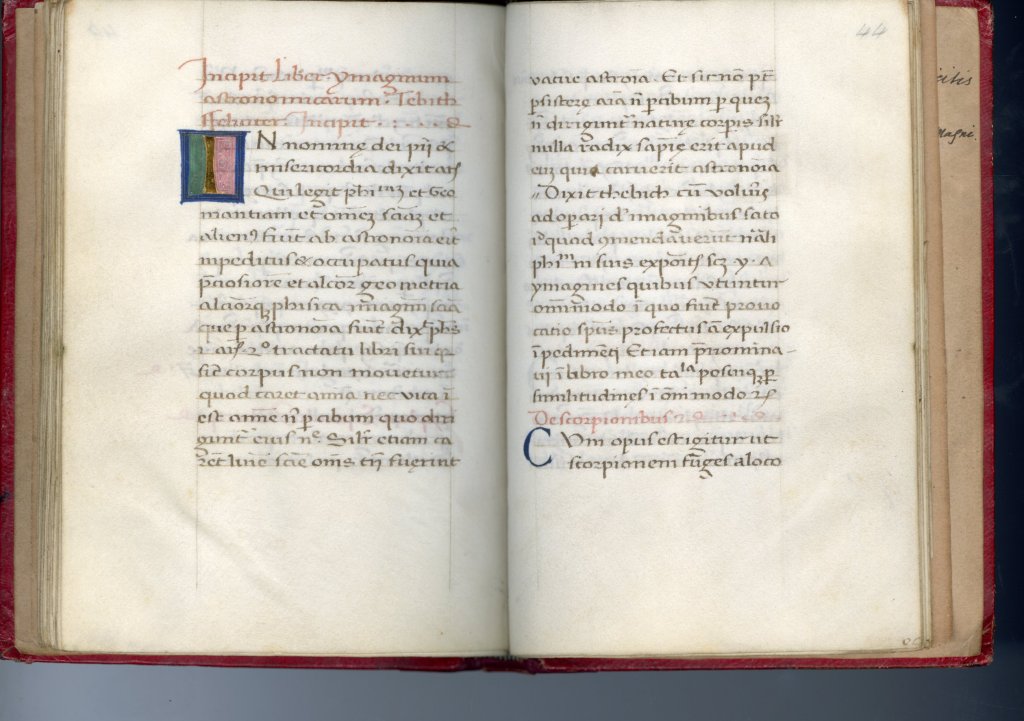

This treatise begins with another incipit in red: ‘Incipit Liber ymaginum astronomicarum. Tebith.’ ‘Here begins a book on astronomical images by Thabit’. We have another illuminated letter, this time an I, as the manuscript begins ‘In nomine dei’ (‘In the name of God’).

Thabit ibn Qurra was born in Mesopotamia circa 830 CE. He wrote over 150 works on subjects from medicine to mathematics and from astrology to geometry. Thabit was trilingual in Syriac, Arabic and Greek, and founded a school of translation in Baghdad. Like Albertus after him, Thabit was responsible for preserving ancient Greek texts, and produced translations of Euclid, Ptolomy and Archimedes. He is known in the history of mathematics for his work on number theory, and he also updated Ptolomy’s theories of astronomy. In the late 9th century, Thabit was appointed court astronomer to Caliph al-Mu’tadid, and this treatise documents his work on the theory of astrological images, or talismans.

Talismans were objects inscribed with, or in the shape of, astrological symbols such as the signs of the zodiac. Their power was based on the influence of the moving planets and stars on people and events, as discussed by Albertus Magnus under the heading of astrology. The process of making the talisman imbued the item with celestial power.

Thabit’s treatise contains detailed instructions for making and using talismans. One example, also discussed in the Speculum, is a talisman that draws on the power of the sign of Scorpio. If you made a metal cast in the shape of a scorpion, when the zodiac sign was in the ascendant, and buried it in the foundations of a building, it would protect the inhabitants against scorpion bites.

Fragments of this section of the manuscript in its original Arabic were recently discovered at the University of Cambridge.

Three scientists, one manuscript

Albertus Magnus, Thabit ibn Qurra and Thompson have more in common than this single manuscript. All three were translators: Albertus and Thabit translated Greek texts, while Thompson produced an English translation of William Gilbert’s De Magnete (he was also fluent in German and French, and spoke a little Italian). All three understood the importance of identifying and preserving historic scientific texts for future scholars. And all three produced practical guides. Thompson wrote texts on engineering and mathematics for his students, Albertus developed a framework for the use of Greek and Arabic philosophy in medieval education, and Thabit wrote texts on astronomy, mathematics, medicine – and talismans.

Further reading

Paolo Zambelli, The Speculum Astronomiae and its Engima (Dordrecht, 1992)

Gideon Bohak and Charles Burnett, Thabit ibn Qurra On Talismans (Sismel, 2021)

Charles Burnett, ‘On the theory and practice of talismans‘ (talk to the Warburg Institute)