On this day in (engineering) history…

March 11, 2011 – The Fukushima Disaster – Earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear accident in one.

The most powerful earthquake in Japanese history caused a massive tsunami, three nuclear meltdowns, the deaths of nearly 20,000 people, with another 6,000 people injured and 2,500 people missing. Even ten years later, almost a quarter of a million people were still living in temporary accommodation of one sort or another.

This was the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami (the Great East Japan Earthquake, or 3.11 – san ten ichi-ichi in Japanese), which swamped 2,000km (1,242 miles) of Japan’s northeast coast. It also caused the most serious nuclear accident since the explosion at Chornobyl in 1986.

Powers greater than we can imagine

On the cold, wintery afternoon of March 11, 2011, 72km from Tōhoku prefecture’s Oshika peninsula at a depth of 32km (20 miles), the North American tectonic plate slid twenty metres horizontally over the western edge of the Pacific plate across a front of 650km. This 9.0 Mw megathrust earthquake released 600 million times more energy than the Hiroshima The tsunami at Miyako, 2011. Source: Wikimedia Commons. atomic bomb, moving an area of seabed covering 200 km by 400 km.

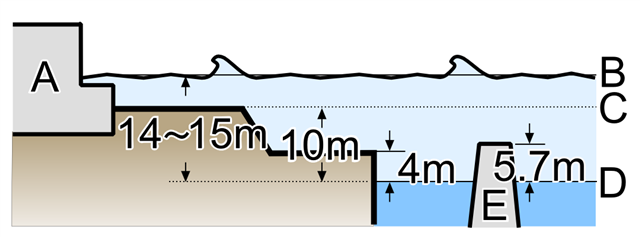

Fifty minutes later, workers faced a wall of water up to fourteen metres (46 feet) high at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant further down the coast, near Okuma. Even though the plant was ten metres (33 feet) above sea level, it was still lower than the top of the waves.

It looked like a good idea back then

There were two nuclear power stations on the coast of Fukushima Prefecture – Fukushima Daiichi (One) and Fukushima Daini (Two) 11km further down the coastline.

Construction began on Fukushima Daiichi in 1967, before being commissioned in 1971. Tokyo Electric Power Company (Tepco) operated the facility, which featured six boiling water reactors of different iterations, built by General Electric between 1970 and 1979. Reactor

The height of the tsunami that struck the station 50 minutes after the earthquake.

A: Power station buildings

B: Peak height of tsunami

C: Ground level of site

D: Average sea level

E: Seawall to block waves

Reactor Numbers 1 to 3 were still operational; Number 4 had become a temporary storage for spent nuclear fuel, while Numbers 5 and 6 were not operational. The design of the units gave them a tolerance for ground acceleration of up to 470 Gal.

Earth moving

Japan is highly seismologically active, with a frequent risk of tsunamis, of which there have been devastating examples going back over millennia. The original designers had accounted for this by setting the plant ten metres above the water level and protecting it with a five-metre-high sea wall.

When the shaking began, control rods were automatically inserted into the reactor cores to stop fission reactions, but the reactors still needed cooling.

To keep reactor units cool during an emergency, operators would pump water into the reactors themselves. The resulting steam would be only slightly radioactive because the fuel would still be in the primary containment vessel. Opening a manually operated valve would prevent a high-pressure build-up and lower the risk of an explosion.

Getting out of hand

Now that the reactors had shut down, there was no electricity to continue the cooling process.

Now that the reactors had shut down, there was no electricity to continue the cooling process.

Six external lines from the grid would typically provide a backup electricity supply, but the earthquake destroyed them. The next step was to switch to the water-cooled emergency diesel generators placed in a basement some metres below the level of the reactors. Water pumps placed on the shoreline provided the coolant.

Then the tsunami, with its wall of fast-moving water, struck the plant, and the 5.7-metre-high seawall had no effect on the 14-metre-high waves. (For comparison, in the 1970s, the mayor of Fudai, a fishing village on the north-east coast, persuaded his council and population to build a 15.5-metre high floodgate and seawall. This was enormously expensive and for many years was seen as a folly. Until March 11, 2011. The village was untouched by the tsunami, where nearby coastal towns and villages were severely damaged.)

Fighting the system

The wave knocked out eleven of the plant’s twelve generators, destroying the seawater pumps in the process. Losing the pumps ended the heat transfer from the reactor cores to the sea. Now, there would be no way to cool the reactors.

The next option was to switch to emergency battery power. DC batteries equipped each reactor in the event of an emergency. Flooding put the batteries at units 1 and 2 out of action, leaving only Unit 3’s battery in working order. The battery lasted thirty hours, against a designed eight-hour running time.

During the next three days, one after the other, each operating reactor lost its cooling. When this happens, the water in the reactor pressure vessel eventually boils, uncovering the fuel rods within the reactor. Next, the fuel overheats and melts, creating ‘corium,’ a mix of melted fuel and reactor components. The risk now was that this corium would burn through the steel reactor pressure vessel, the concrete and steel primary containment vessel and onto the bare earth below.

During the next three days, one after the other, each operating reactor lost its cooling. When this happens, the water in the reactor pressure vessel eventually boils, uncovering the fuel rods within the reactor. Next, the fuel overheats and melts, creating ‘corium,’ a mix of melted fuel and reactor components. The risk now was that this corium would burn through the steel reactor pressure vessel, the concrete and steel primary containment vessel and onto the bare earth below.

When the boiling water turned to steam, it built up pressure inside the primary containment vessel, creating leaks and allowing radiation into the atmosphere. To reduce this pressure, workers also vented some of the radioactive steam, which would prove futile when hydrogen gathered in the buildings of Reactor 1 and 3 exploded, blowing off their roofs. Unit 4 could have exploded for the same reason - a build-up of hydrogen in the roof caused by a common venting system.

A history of violent earthquakes

Japan is one of the most seismically active countries on the planet. Earthquakes are common, and so are tsunamis.

Japan is one of the most seismically active countries on the planet. Earthquakes are common, and so are tsunamis.

Built in the 1960s and 1970s to standards in force at the time, the Fukushima Daiichi was outdated in 2011. By 1993, more knowledge and data suggested the area was at great risk from a major earthquake accompanied by a 15.7-metre tsunami. Neither Tokyo Electric Power Company (Tepco) nor the Nuclear & Industrial Safety Agency (NISA) acted on the information.

International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) standards - such as placing emergency diesel generators higher up the hillside, backup for the shoreline water pumps and sealing the lower areas of the buildings – were also ignored.

The struggle

Conditions on the site as workers attempted to control the situation were appalling. Strewn across the plant was debris from the tsunami and the subsequent explosions that ripped apart buildings and damaged temporary emergency equipment rigged up to save the site. In the control rooms for units 1 and 2, instrumentation had completely failed, some of which was restored three hours after the tsunami. By then, it had become clear the emergency cooling system was not working. Fuel was about to melt.

There was one landline telephone connection between the emergency control centre and the reactor unit control rooms. Workers searched the site for cables, car batteries and any electrical components to power instrumentation in the control room for units 1 and 2. The unit 2 side of that room was in total darkness, so working conditions were more demanding.

All this work had to be carried out in full protective gear with breathing apparatus in a highly radioactive environment. Then there is the stress of dealing with such a situation in such a facility under such conditions.

Evacuation

The lack of tsunami preparedness made matters worse. Emergency workers abandoned the off-site emergency response HQ because it was so poorly prepared.

The lack of tsunami preparedness made matters worse. Emergency workers abandoned the off-site emergency response HQ because it was so poorly prepared.

At 7:03 PM, on March 11, the authorities declared a Nuclear Emergency and ordered the evacuation of people within a two-kilometre radius of the plant. At 9:23 PM, the Prime Minister, Shinzo Abe, increased this to a three-kilometre radius. At 5 AM the next day, three kilometres became ten kilometres. After he visited the plant on March 12, Abe ordered a 20-kilometre exclusion zone.

In all, the wave killed three workers when it struck the plant. Sixteen others needed hospital treatment for radiation poisoning, while another died from cancer four years later.

Afterwards, the authorities – Tepco and NISA – came under enormous criticism for their performance leading up to the disaster. Japan decided to end its use of nuclear power.

Evacuation zone after the nuclear accident at Fukushima Daiichi, 2011. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Share your thoughts

How easy is protecting nuclear facilities from natural disasters, now and in the future? Share your thoughts in the comments below

By Stephen Phillips - IET Content Producer, with passions for history, engineering, tech and the sciences.

By Stephen Phillips - IET Content Producer, with passions for history, engineering, tech and the sciences.