This June will mark five years since the Grenfell tragedy, which shocked everyone and challenged us to think again about how our industry works. But how far have we come, and what is stopping us?

This article argues that there can be no building safety without transparency and integrity, and we need to take a different approach.

Call Reschedule: Due to technical issues we had to postpone our call to discuss this article. The call will now take place on Teams on Friday 4th March at 2.30pm GMT. Please register here to join us.

The Context

The Grenfell Inquiry, now in module 6 of phase 2, is looking at the role of regulators and government in the failures which led to the tragedy. Week after week the Inquiry reveals more about what led to the catastrophic results of failure. It is painful, embarrassing, and difficult to watch. All the time, the list of organisations to blame gets longer, and the image of the industry gets worse. What does finger pointing achieve?

Last month the Industry Safety Steering Group published its third report to government on Building Safety, to which government responded,

“The report highlights areas of good practice, particularly in industry-wide initiatives, but finds that we are yet to see a critical mass of industry players demonstrating the leadership necessary to accelerate the pace of change and rebuild trust in the sector.”

Dame Judith Hackitt was reported in the CIOB publication Construction Management in January, saying:

“It has been crystal clear to many of us from the outset that legislation alone will not deliver the outcomes we are looking for. The culture of the industry itself must change to one which takes responsibility for delivering and maintaining buildings which are safe for those who use them.”

She praised initiatives such as the Building a Safer Future Charter and the Code for Construction Product Information but said there was only limited take up of these initiatives and added,

“It is time to differentiate between those who are ready and willing to do the right thing and lead the way and those who continue to try and hide.”

Are you trying to hide? We don’t think you are. There is something else going on.

Other Tragedies and the Relaxation of Standards

We mustn’t look at Grenfell in isolation. Here are just a few other examples of building safety failures from recent years:

- Knowsley Heights Fire, Liverpool, April 1991

- Lakanal House Fire, London, July 2009

- Ponte Morandi Viaduct Collapse, Milan, August 2018

- Tower block gas explosion, Presov, Slovakia, December 2019

- Torre del Moro Fire, Milan, August 2021

- New Providence Wharf Fire, London, April 2021

- The Batumi Tragedy, Batumi, Georgia, October 2021

- Surfside Condominium Collapse, Miami, Florida, June 2021

- Twin Parks Fire, The Bronx, New York, January 2022

Decades of building deregulation, complexity of the supply chain, lack of transparency and integrity, and particularly a shift to a more flexible interpretation of standards motivated by commercial pressures, are a major cause of these tragedies. We are not seeking to blame individual organisations, but we do need to understand the structural implications of the commercial and political pressures on our industry.

What is Building Safety and why does it Matter?

The Building Safety Bill will be the foundational, governing framework of building safety when it comes into law.

The Bill defines building safety risks as

“fire spread (for example, from one flat to another or one floor to another) and structural failure”.

It is important to realise that the Bill will apply to all buildings, not just high rise.

Setting the Bar, published in October 2020 by the Construction Industry Council defined ‘Building safety’ as,

“…the major safety hazards that might result in multiple casualties, principally fire safety and structural safety of a building. Other safety hazards may be considered where these have potential to impact on the fire safety of a building, such as electrical and gas safety.”

Ensuring building safety means making judgements about risk. One cannot make accurate judgements about risk without reliable, accurate information.

It seems perverse to ask why building safety matters, but it is an important question if we want to understand why it isn’t happening to some of our buildings.

- Firstly, the industry has major issues with delivering performance. Poor performance leads to poor build quality and subsequent disasters and human tragedies.

- Secondly, we know that there are major skills, competency and resource issues, worsened by the ageing population and restrictions on imported labour.

- Thirdly, there is the challenge of risk management, with risk being transferred down the construction management chain whilst profits are squeezed.

These factors, combined with the revelations of Grenfell, are contributing to a lack of trust in the whole process of procuring a building – and living and working in one.

If you buy a building with failures, you appear to have no legal recourse to the seller, as many leaseholders and clients have recently discovered. And the implications can be complex, reflecting the complexity of the risk and responsibility network that is construction.

When you buy a beach, you buy every grain of sand.

Causes of our problems

The Farmer Review (Modernise or Die, 2018) set out ten ‘critical symptoms’ of failure and poor performance in construction and the built environment. Ten.

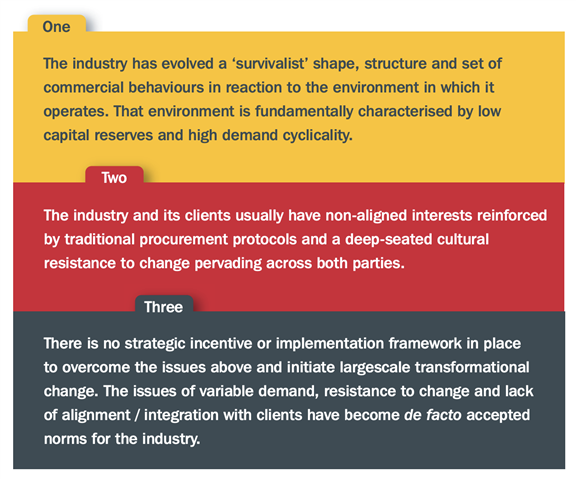

Sitting behind those ten characteristics, Farmer argued, are three root causes – commercial, cultural and strategic:

Farmer’s review was written a year before the Grenfell tragedy and was motivated by the challenge of a failed labour model. Five years on he felt that whilst his predictions seemed over dramatic at the time, if anything they were under estimated.

We know that there are structural problems with our industry. Is it possible for us to change them?

Farmer’s treatment plan recommended

- Client led change because ‘the industry will not change itself unilaterally at scale’.

- A tripartite covenant between construction, end clients and government acting as strategic initiator.

- Modern methods of construction to deal with the labour and productivity challenge.

The government accepted 9 out of 10 of Farmer’s recommendations, refusing to impose a client levy. Through the £170m Construction Sector Deal in 2017 it set up the Construction Innovation Hub, initiated a reform of the Construction Industry Training Board and set up a skills strategy and a retraining scheme. This strategy was adjusted when a new government came into power in 2019.

Farmer’s diagnosis was good, but the treatment plan didn’t produce significant changes, or at least, not yet. £170m is a catalytic amount, not an industry changing amount of funding. Just one major manufacturer we know who is adopting a digital strategy is spending £50-60m over the next five years. We cannot expect government to fund us out of this problem.

Poor information control contributes to many of the symptoms Farmer outlined five years ago –

- It reduces productivity and predictability and damages the image of the sector.

- It discourages collaboration and improvement.

- It prevents access to the information that can inform and motivate leadership, research and investment and innovation.

Is the System Broken?

A fish is swimming along one day when another fish comes up and says, ‘Hey, how’s the water?’ The first fish stares back blankly at the second fish and then says, ‘What’s water?’

Kania, Kramer and Senge (2018). The waters of systems change, p. 2.

In her 2021 book, Catastrophe and Systemic Change, Gill Kernick uses the analogy of a fish not knowing what water is, to explain why systemic change is such a difficult concept to understand. If the system we are so familiar with, is broken, we cannot necessarily see why it is broken and therefore how to fix it. Because we take it for granted that we know what is going on, we can miss the complex matrix of causes.

Kernick’s book is a forensic analysis of Grenfell as a systemic failure by an author outside the construction industry who has consulted in other high-risk industries and on other tragedies such as the Piper Alpha disaster. She came to write about our industry from the outside because of a personal connection with the residents of Grenfell, and her perspective is therefore not only well informed but refreshingly new. Even now we do not know the scale of the failure in high rise buildings. Our traditional methods of looking internally for solutions are not enough; we need to learn from elsewhere.

Kernick says the system is not broken; it is working perfectly to fulfil its objectives. It is simply that those objectives are not those that would lead to building safety. To deal with systemic failure we need to take a systemic approach, not a piecemeal one. We need to look at the whole.

What does Systemic Change Mean?

In an interview with the BBC shortly after the fire, Gill Kernick said,

‘We have to get beyond blame to the systemic, cultural and leadership issues that actually led to decisions being made.’

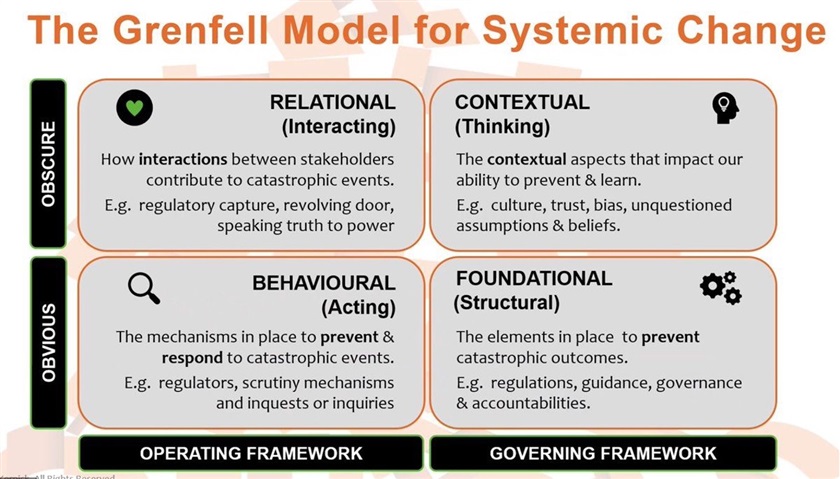

The above diagram, taken from Kernick’s presentation to the London Constructing Excellence Club in January this year, sets out areas that are missing from our analysis of the reasons why catastrophic failures happen. We are familiar with the structural, regulatory elements, but less familiar with the behavioural, relational and contextual elements.

Farmer called for major changes in the nature of the industry on a structural level, such as the expansion of modern methods of construction, fixing the labour crisis via training and investment. Kernick calls on us to make cultural changes to the industry, which means looking at what is preventing individual, human decisions to change.

Transparency and Integrity

In our last article we said that “Transparency will be essential in a post-Grenfell, climate aware, built environment sector”.

- Transparency means knowing what one is dealing with and sharing what one is doing.

- You cannot be transparent if you are unwilling to share what should be publicly available.

- Supply chain transparency brings this concept structurally into the construction industry. Where else could information transparency bring benefits? What is preventing it?

- To achieve transparency of information exchange, what are the foundational changes we need (such as standards and protocols) and what are the human changes we need (such as behaviour)?

In our last article we talked about data integrity as “a critical requirement of a successful data system”.

- Integrity means being able to trust that the information you have access to is totally reliable.

- You cannot buy integrity by ticking boxes and paying a subscription fee.

- Data integrity is the maintenance of, and the assurance of, data accuracy and consistency over its entire life cycle. How can this help us?

- To achieve data integrity, what are the foundational changes we need, and what are the human changes we need?

In the Plain Language Guide (page 3) we tell a story of a data journey which demonstrates how all the individuals involved in the choice, purchase, installation and inspection of a construction product can act with personal integrity and yet a catastrophe can still happen without transparency and integrity of data about the product.

We believe that 90% or more of construction professionals want to do the right thing. Data transparency and integrity can make this possible and would also take care of the 10% or fewer who may be tempted not to do the right thing.

How do we create Transparency and Integrity? Join the Conversation on our open Teams Call

If transparency and integrity are essential to building safety, how do we enable them? We would like to hear your views.

Join us on Teams to discuss this article on Friday 25th February at 2.30pm. Sign up here for your place.

Call Reschedule: Due to technical issues we had to postpone our call to discuss this article. The call will now take place on Teams on Friday 4th March at 2.30pm GMT. Please register here to join us.

“We are spending all this energy listening to leaders who are measuring the size of the mountain instead of talking to those that can motivate to move it.”

The guide aims to help decision-makers in manufacturing identify:

- Why structured data is important.

- How to avoid poor investment decisions.

- How to protect their future with a step by step process to set priorities and implement information management across the supply chain for their products.

Read the guide here:

Check out our tweets at #ManufacturersPLG.